Even amongst people with bipolar disorder, the disorder is highly contested. People argue about what it’s “really” like to have bipolar disorder. What mania is like. What depression is like. And perhaps most hotly debated of all is what the appropriate treatment of the symptoms is – antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, psychotherapies, alternative treatments and so on. People argue about virtually everything.

And one of the reasons why this is the case is because the experience of bipolar disorder is so vastly different. Some people experience manic psychosis, others do not. Some people experience delusional depression, others do not. Some people experience suicidality, others do not. And so on. Severity varies as do symptoms.

And I would argue that much of this disagreement stems from the two basic types of bipolar disorder: well-controlled and not well-controlled bipolar disorder.

Understanding Mental Illness

Bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder have crossover traits and so a person with bipolar disorder can often mistakenly be diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. In fact, some feel that diagnosis with both disorders is inappropriate unless the patient’s bipolar disorder is in remission.

But some people do meet the diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. I would have put this number much lower than it actually is thought to be. From the research I’ve done, it appears that borderline personality disorder is comorbid to bipolar in around 40% of cases. This is particularly surprising as it was once thought that personality disorders were only comorbid to bipolar in 12% of cases or less.

But what is borderline personality disorder and what does it mean if you’re diagnosed with both bipolar and borderline personality disorder?

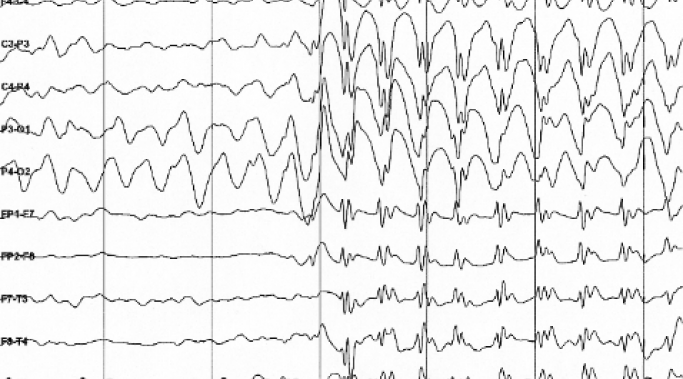

Recently, it was announced that the very first diagnostic brain scan for a mental illness became Food and Drug Administration-approved. This test uses electroencephalography (EEG) to diagnose attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Finally, people with a mental illness (in this case ADHD) can point to a biological test and say, look – see – my disorder is biological in nature and we can test for it.

It’s not terribly surprising that ADHD is the first disorder to have this type of test as we understand an ADHD brain better than we understand a brain with other disorders. Nevertheless, it won’t be the last. Scientists are actively working on diagnostic tests for depression, autism, bipolar and schizophrenia too.

And while I consider this a major breakthrough in our real, tangible understanding of mental illness, there are reasons why diagnosis by brain scans matters and reasons why it doesn’t.

Delusions are false beliefs that are held in spite of a lack of evidence or even evidence to the contrary. For example, a delusion might be believing that the FBI is surveilling you every day or that you can predict the future. Delusions are a part of psychosis which can be present in bipolar depression or bipolar mania.

Delusions are easiest to spot when they’re exaggerated, like in the above examples, but I would suggest that delusions are much more common when we give them credit for. I would suggest that delusions are present in most cases of severe bipolar depression.

One of the most controversial things the latest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) did was remove the bereavement exclusion from the depression diagnosis. Previously, people grieving the loss of a loved one couldn’t be diagnosed with depression for two months after the loss. Now, however, this is no longer the case. Now, even a person grieving the loss of a loved one can be diagnosed with depression.

And some people say this is a further medicalizing of normal emotion. I, however, would argue that there was a good reason for this change and that skilled clinicians can tell the difference between grief and depression. Here are some ways grief and depression differ.

A normal life is something I’m not very familiar with. I’ve never really had one. From the time I was a kid with an alcoholic father, to the teenage years I spent depressed, to my adult years dealing with psychiatrists, symptoms and medication side effects, I’ve never really enjoyed anything termed normalcy.

But the question is, does anyone with bipolar enjoy a normal life?

Bipolar places limitations on our lives. It might be the fact that we can’t go out and enjoy a cocktail after work or it might be the fact that we can’t stay out all night. Or it might be the fact that we can’t work full time or that we have to live with medication side effects that make us sick. Limitations are there, no matter how you look at it.

But what happens when you don’t respect those limits? What happens when you choose to ignore them?

I can tell you. You feel like a dog’s breakfast. Just ask me. I did it on Monday.

While it seems hard to believe, some people want others to stay mentally ill and, indeed, sometimes even individuals themselves, choosing to maintain mental unwellness. You have the obvious example of people refusing medication and thus becoming very sick but there are other forces as well that can encourage a person to stay acutely, mentally ill.

When I speak to kids about my experience with bipolar disorder, really, I have a series of failures to explain. I tell them how treatment after treatment failed. I talk about drug failures, the failure of the vagus nerve stimulator and the failure of electroconvulsive therapy. I lot of my sentences have the word, “unfortunately,” in them.

And after one of my presentations last week, one person asked what I would say to someone who was going through a similar experience. I thought that was a very important question.

So here’s what I would say to someone who’s experiencing treatment failure.

A reader recently contacted me and asked me about psychomotor agitation. Psychomotor agitation is actually a symptom of bipolar hypomania and bipolar mania (and depression) and yet few people know what this means. In fact, according to this study, it is poorly defined and measured even within the medical community. Psychomotor agitation is often translated into “restlessness,” which doesn’t seem overly descriptive to me.

So here’s my take on psychomotor agitation: how it feels and what we know about it.

![MC900441394[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2013/08/MC9004413941.png?itok=UHwwmyXi)

![MP900405644[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2013/06/MP9004056441-1024x685.jpg?itok=sLTFbNTj)

![MP900390526[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2013/05/MP9003905261.jpg?itok=8oVaR4Fn)

![MP900387479[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2013/05/MP9003874791.jpg?itok=H3noVYZU)