How to Handle a Suicide Threat - For Teens

What would you do if one of your friends threatened to commit suicide? If someone you know is suicidal, here's what to do.

- Danger Signs of Youth Suicide

- If You Are Confided In - What to Do

- Get Help For a Suicidal Person

- What About You

- Warning Signs of Suicide

- What to Do If Someone is Threatening Suicide - Things That Can Help

What would you do if one of your friends threatened to commit suicide?

- Would you laugh it off?

- Would you assume that the threat was just a joke or a way of getting attention?

- Would you be shocked and tell him or her not to say things like that?

- Would you ignore it?

If you reacted in any of those ways you might be missing an opportunity to save a life, perhaps the life of someone who is very close and important to you. You might later find yourself saying, "I didn't believe she was serious," or "I never thought he'd really do it."

Suicide is a major cause of death. The American Association of Suicidology estimates that it claims 35,000 lives each year in the United States alone; authorities feel that the true figure may be much higher. A growing number of those lives are young people in their teens and early twenties. Although it is difficult to get an accurate count because many suicides are covered up or reported as accidents, suicide is now thought to be the second leading cause of death among young people.

If someone you know is suicidal, your ability to recognize the signs and your willingness to do something about it could make the difference between life and death.

Danger Signs of Youth Suicide

No doubt you have heard that people who talk about suicide won't really do it. It isn't true. Before committing suicide, people often make direct statements about their intention to end their lives, or less direct comments about how they might as well be dead or that their friends and family would be better off without them. Suicide threats and similar statements should always be taken seriously.

People who have tried to kill themselves before, even if their attempts didn't seem very serious, are also at risk. Unless they are helped they may try again, and the next time the result might be fatal. Four out of five persons who commit suicide have made at least one previous attempt.

Perhaps someone you know has suddenly begun to act very differently or seems to have taken on a whole new personality. The shy person becomes a thrill-seeker. The outgoing person becomes withdrawn, unfriendly and disinterested. When such changes take place for no apparent reason or persist for a period of time, it may be a clue to impending suicide.

Making final arrangements is another possible indication of suicidal risk. In young people, such arrangements often include giving away treasured personal possessions, such as a favorite book or record collection.

What To Do If Someone Tells You They Want to Kill Themselves

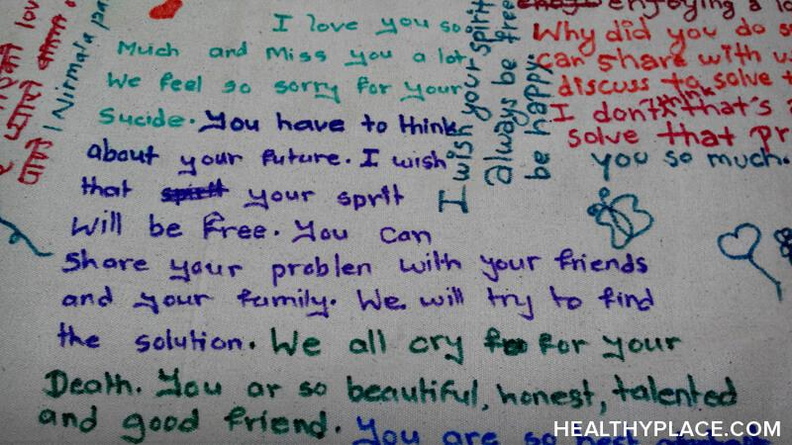

If someone confides in you that he or she is thinking about suicide or shows other signs of being suicidal, don't be afraid to talk about suicide.

Your willingness to discuss it will show the person that you don't condemn him or her for having such feelings. Ask questions about how the person feels and about the reasons for those feelings.

Ask whether a method of suicide has been considered, whether any specific plans have been made and whether any steps have been taken toward carrying out those plans, such as getting hold of whatever means of suicide has been decided upon.

Don't worry that your discussion will encourage the person to go through with the plan. On the contrary, it will help him or her to know that someone is willing to be a friend. It may save a life.

On the other hand, don't try to turn the discussion off or offer advice such as, "Think about how much better off you are than most people. You should appreciate how lucky you are." Such comments only make the suicidal person feel more guilty, worthless, and hopeless than before. Be a concerned and willing listener. Keep calm. Discuss the subject as you would any other topic of concern with a friend.

Get Help for a Suicidal Person

Whenever you think that someone you know is in danger of suicide, get help. Suggest that he or she call a suicide prevention center, crisis intervention center or whatever similar organization serves your area. Or suggest that they talk with a sympathetic teacher, counselor, clergyman, doctor or other adult you respect. If your friend refuses, take it upon yourself to talk with one of these people for advice on handling the situation.

In some cases you may find yourself in the position of having to get direct help for someone who is suicidal and refuses to go for counseling. If so, do it. Don't be afraid of appearing disloyal. Many people who are suicidal have given up hope. They no longer believe they can be helped. They feel it is useless. The truth is, they can be helped. With time, most suicidal people can be restored to full and happy living. But when they are feeling hopeless, their judgment is impaired. They can't see a reason to go on living. In that case, it is up to you to use your judgment to see that they get the help they need. What at the time may appear to be an act of disloyalty or the breaking of a confidence could turn out to be the favor of a lifetime. Your courage and willingness to act could save a life.

For Younger Kids and Teens - Get Help

If a friend is talking about suicide or displaying other warning signs, you can start by listening to and reassuring him. Then, even if you're sworn to secrecy and you feel like you'd be betraying your friend if you told someone, you should seek help. This means sharing your concerns with an adult you trust as soon as possible. If necessary, you can also call a local emergency number or the toll-free number of a suicide crisis line.

The important thing is that you notify a responsible adult. Although it may be tempting to try to help your friend on your own, that may not be possible, and the delay in getting an adult's help could be risky to your friend's well-being.

What About You? Have You Thought About Suicide?

Perhaps you yourself have sometimes felt like ending your life. Don't be ashamed of it. Many people, young and old, have similar feelings. Talk to someone you trust. If you like, you can call one of the agencies mentioned above and talk about the way you feel without telling them who you are. Things seem very bad sometimes. But those times don't last forever. Ask for help. You can be helped. Because you deserve it.

Warning Signs of Suicide

- Suicide threats

- Statements revealing a desire to die

- Previous suicide attempts

- Sudden changes in behavior (withdrawal, apathy, moodiness)

- Depression (crying, sleeplessness, loss of appetite, hopelessness)

- Final arrangements (such as giving away personal possessions)

What To Do - Things That Can Help

- Discuss it openly and frankly

- Show interest and support

- Get professional help

Prepared by the Suicide Prevention and Crisis Center of San Mateo County, California, in cooperation with the American Association of Suicidology.

APA Reference

Tracy, N.

(2022, January 11). How to Handle a Suicide Threat - For Teens, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, November 10 from https://www.healthyplace.com/depression/articles/how-to-handle-a-suicide-situation-for-teens

Why Do Teens Commit Suicide? Causes of Teen Suicide

When a suicide occurs, people want to know, why do teens commit suicide? Some people consider their teenage years the happiest years of their lives, so a teen suicide just doesn't make sense to them. But teens can suffer real pain and be in terrible situations and these can cause teen suicides.

Why Do Teens Commit Suicide? Emotional Causes

Most teens who have been interviewed after a suicide attempt say that what causes teen suicide are feelings of hopelessness and helplessness. Suicidal teens often feel like they are in situations that have no solutions. The teens can see no way out but death. The teens feel like they have no control to change their situations.

Other emotional teen suicide causes stem from trying to escape feelings of pain, rejection, hurt, being unloved, victimization or loss. Teens may feel like their feelings are unbearable and will never end, so the only way to escape is suicide.

Teens may also be afraid of disappointing others or feel like they are a burden to others, such as their parents, and these can be additional causes of teen suicide.

Teen Suicide Causes – Environmental Causes

Situations often drive the emotional causes of suicide. Bullying, cyberbullying, abuse, a detrimental home life, loss of a loved one or even a breakup can be contributing causes of teen suicide. Often, many of these environmental factors occur together to cause suicidal feelings and behaviors.

Ethan felt like there was no point going on with life. Things had been tough since his mom died. His dad was working two jobs and seemed frazzled and angry most of the time. Whenever he and Ethan talked, it usually ended in yelling.

Ethan had just found out he'd failed a math test, and he was afraid of how mad and disappointed his dad would be. In the past, he always talked things over with his girlfriend — the only person who seemed to understand. But they'd broken up the week before, and now Ethan felt he had nowhere to turn.

Ethan later went on to seek out his dad's gun with which to attempt to take his life.

As in the above example, it is typical that many factors – both emotional and environmental – contribute to the cause of teen suicide or teen suicide attempt.

Mental Illness as a Cause of Teen Suicide

While all the above are driving factors of teen suicide, often the underlying issue is one of mental illness. Most teens who attempt suicide do so because of depression, bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder. These disorders amplify the pain a teen may feel. It is because of this that any suicidal teen should be treated by a medical professional.

Why Teens Commit Suicide

What's important to remember is that teens attempt or commit suicide not because of a desire to die, but, rather, in an attempt to escape a bad situation and/or painful feelings. It's rare that only a single event leads to suicide. This means that by helping a teen turn around a bad situation or by teaching her or him how better to deal with painful feelings, we can defeat the causes of teen suicide.

Most times, this requires professional help by a doctor or a psychotherapist and may also involve the teen's school, such as in cases of teen bullying.

APA Reference

Tracy, N.

(2022, January 11). Why Do Teens Commit Suicide? Causes of Teen Suicide, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, November 10 from https://www.healthyplace.com/suicide/why-do-teens-commit-suicide-causes-of-teen-suicide

What To Do If Your Teen May Attempt Suicide

If you have spotted the signs of possible suicide in your teen and you fear that your child may make a teen suicide attempt, you may be scared and not know what to do. This is normal. There is no chapter in a parenting handbook on dealing with a suicidal teen.

Nevertheless, what you do next is very important to avoid an attempted suicide in a teen. Start by not ignoring the problem and vowing to take proactive steps to protect your teen from possible harm.

If your teen is in immediate danger from suicide, do not wait, dial 9-1-1 or take them to an emergency room immediately.

How To Avoid a Teen Suicide Attempt

Talk To Your Teen About Suicide

It's critical to not be dismissive about possible suicidal feelings and open up a dialogue with the teen about suicide. Remember, talking about suicide does not increase the chance of a teen suicide attempt. How you talk about suicide is very important, though. According to an expert on teen suicide, Nadine Kaslow Ph.D., follow these guidelines when talking to a teen about their thoughts of suicide:

- Talk about your concerns in a calm, non-accusatory manner.

- Never simply tell them to stop feeling that way or that it's wrong to feel that way. Validating a teen's feelings is very important, even if you don't necessarily understand them.

- Tell and show your child that you still love him or her. Don't just assume that he or she knows this already.

- Express empathy for a teen's pain by saying things like, "that sounds like that was very difficult," or "I know that can be painful."

- Encourage the teen to get professional help and reinforce the fact that feeling this way or getting help is not a sign of weakness.

- Tell the teen you will work with him/her to get the help needed and that you respect the teen for taking that step.

Often teens are driven to suicide because they feel hopeless and like things will never get better. Try to affirm the opposite by creating positive moments in your teen's life. It can be easy to fall into a pattern of being critical of a teen, rather than showing true concern, so try to act in more positive ways by doing fun things together and chatting about things that won't bring up strong emotional responses.

Get Help to Avoid a Teen Suicide Attempt

Once you've started a conversation with your teen about suicide, it's important to get the teen professional help. You, as a parent, can be great support but that isn't the same thing as addressing this serious issue.

The best thing to do is to get a referral to a child psychologist or child psychiatrist from your family doctor or get recommendations from a school counselor, if available. You should always seek out a professional who specializes in working with suicidal teens, as not all mental health professionals will feel comfortable in that area. If you feel your teen cannot wait for treatment, it may be time to consider hospitalization or partial hospitalization until outpatient treatment can commence. Suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts in teens are emergencies and need to be treated that way.

You and your teen may need to interview several professionals before you find one that you and your teen are comfortable with. This healthcare professional may literally have your teen's life in his or her hands, so it's important to take your time and choose wisely.

Once a professional has been selected, everyone in the family should take an active role in your teen's mental health treatment. It's critical that the teen know that everyone is supportive and that he or she is loved and cared for. This could mean bringing everyone in the family in for family therapy.

Different kinds of therapy, and possibly medication, may be used to treat a suicidal teen depending on the underlying issue. For example, if a teen has borderline personality disorder, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) has shown positive results in reducing teen suicides. If a teen has depression or bipolar disorder, medication may be prescribed to help improve his or her mood. In many cases, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can be used to decrease suicidal thoughts and feelings.

The important thing to remember is that help is available to avoid teens from attempting suicide. Your teen does not have to become a statistic.

APA Reference

Tracy, N.

(2022, January 11). What To Do If Your Teen May Attempt Suicide, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, November 10 from https://www.healthyplace.com/suicide/what-to-do-if-your-teen-may-attempt-suicide

Parenting Tips for When Your Tween Has a Meltdown

When your tween has a meltdown, chances are you could use some practical parenting tips for handling your pre-teen and their behavior. It can be shocking to witness a meltdown in a 9-12 year-old. After all, aren’t they too old for such behavior? As you’ll see, they’re just the right age for emotional meltdowns. Meltdowns are difficult for these middle schoolers (and upper elementary schoolers), and they’re not exactly easy for parents. These parenting tips will help you when your tween has a meltdown.

Dealing with meltdowns is slightly less difficult when you realize what they are. Meltdowns are reactions to negative, overpowering feelings or overwhelming sensory input. They’re not an attempt to manipulate parents into giving in to a tween’s wishes.

Parenting Tip: Understand Why Your Tween Hasn’t Outgrown Meltdowns

Emotional outbursts in an older child can seem unsettling or perhaps even maddening. Tweens aren’t little kids anymore. On the other hand, they’re not yet teenagers, either. Tweens are caught between childhood and adolescence, not quite fitting into either category. Drastic changes and new experiences can be overwhelming and lead to meltdowns.

Your child’s meltdowns often happen precisely because they’re a tween. They aren’t too old for yelling or slamming doors or throwing things or saying hurtful things. They’re just the right age. Tweens begin to grow and change rapidly. Physical, emotional, cognitive, hormonal, and neurological changes correspond to a desire for more independence and responsibilities. These changes can cause tweens to act out rather than responding rationally to parents and peers.

Other challenges underlying tween meltdowns include:

- Sometimes wanting to return to the simpler days of childhood and other times looking forward to being in high school and close to adulthood

- Feeling left out or disliked by peers, which can be daily in middle school

- Feeling stifled in their efforts to gain some independence

- Frustration and anger that comes from difficult relationships or situations

- A need for understanding from peers, parents, and teachers that sometimes goes unmet

Understanding the reasons why your son or daughter has meltdowns is the first step in de-escalating the intense emotions being expressed. There are other things you can do to help prevent and reduce the breakdown of rational conversations.

Parenting Tips for Dealing with a Tween Meltdown

While it isn’t possible to completely put an end to meltdowns, you can do certain things to reduce them as well as help them be shorter in length. Consider these parenting tips for tween meltdowns:

Be proactive. During non-emotional times, talk with your tween. What upsets them to the point of breaking down? What is going on during a meltdown? Is your middle schooler hungry? Tired? Having problems with peers? Help your tween develop positive coping strategies and stress management that could reduce the number, frequency, and duration of the outburst.

Additional parenting tips for tween meltdowns:

- Cultivate an open, respectful relationship. Listen fully to your tween, accept their feelings and what they have to say.

- Create an atmosphere of trust and safety because tweens need an accepting place to express their emotions without worrying about being judged or punished.

For dealing with a meltdown as it’s happening:

- Avoid trying to rationalize or reason. Using logic to try to talk your tween out of the meltdown will only make things worse for both of you. During meltdowns, tweens are operating strictly from emotions rather than logic.

- Don’t take the behavior personally. Tweens don’t mean what they say during an outburst. Feeling hurt or slighted keeps you from understanding your tween. As a parent, it’s important to remain calm, responding to your tween rather than reacting emotionally.

- Don’t avoid your tween’s feelings or explosive behavior. Let them know that you support them and are by their side. This can reduce anxiety about talking to you and foster a closer relationship.

- Allow your tween to feel and verbally express negative emotions. Not only does this reduce the need for meltdowns, in helping tweens develop emotional intelligence, you’re helping them develop life skills.

- Make use of fresh starts. One a meltdown is over and your tween has had space and time to relax and decompress, communicate that the incident is behind you both and that you’re starting fresh. Make sure you do this completely rather than continuing to bring up the behavior and what caused it. Your tween will feel safe, secure, and confident that they have your love and support.

See your tween for who they are and all their positives. Understand them, support them, and help them process their powerful emotions, and they’ll soon grow beyond emotional meltdowns. In the meantime, remember this insight from a middle school boy with autism spectrum disorder: “Meltdowns are not who I am.” They’re not who your tween is, either.

See Also:

APA Reference

Peterson, T.

(2022, January 11). Parenting Tips for When Your Tween Has a Meltdown, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, November 10 from https://www.healthyplace.com/parenting/parenting-skills-strategies/parenting-tips-for-when-your-tween-has-a-meltdown

Teen Suicide Warning Signs: What Parents Should Look For

Teen suicide warning signs are important for all parents to know so that in the event that a teen shows behavioral or emotional changes, a parent can evaluate any risk of self-harm and possibly prevent a tragedy. If suicide signs are present in a teen, a parent should know that it isn't the parent's fault.

The teen may have underlying issues, such as a mental illness, that could be driving suicidal thoughts and actions. The most important thing is how a parent responds to the presence of the signs of suicide in a teen. If a teen does show suicide warning signs, they should always be taken seriously and evaluated by a professional.

Warning Signs of Teen Suicide

According to You Matter, a website dedicated to youth suicide prevention created by The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, the following are possible signs of teen suicide:

- Talking about one's suicide or wanting to die

- Seeking out ways to kill oneself, such as gaining access to poison or a firearm

- Talking about feelings of hopelessness, helplessness or having no reason to live

- Talking about being in unbearable pain or feeling trapped

- Talking about being a burden to others

- Increasing use of drugs or alcohol

- Acting anxious or agitated

- Taking unusual risks or acting recklessly

- Changes in sleep patterns

- Withdrawing or talking about feeling isolated

- Show rage or seeking revenge

- Displaying extreme mood swings

Additional Signs of Teen Suicide

According to the American Association of Suicidology (AAS), there are specific risk factors for teen suicide as well as factors that protect against suicide.

One specific risk factor for teen suicide is exposure to another's suicide. When one person dies by suicide, those around that person, are more like to attempt/commit suicide themselves. This is known as suicide contagion. Parents should be aware that any teen who has been exposed to a death by suicide has this increased risk.

Other signs of teen suicide, according to the AAS, include:

- Mental illness

- Substance abuse

- Firearms in the household

- Previous suicide attempts

- Non-suicidal self-injury (self-harm)

- Low self-esteem

Daniel Hoover, PhD, a psychologist with the Adolescent Treatment Program at The Menninger Clinic adds that extreme distress over the breakup of a relationship, or conflict with friends, may also be a warning sign of suicide.

Factors that may protect against teen suicide include:

- Family and school connectedness

- A safe school environment

- Reduced access to firearms

- Academic achievement

- Healthy self-esteem

What To Do If You See the Warning Signs of Teen Suicide

Signs of suicide in teens should never go unaddressed or brushed off as "just teen behavior." In fact, according to a 2011 survey, in the previous 12 months, 7.8% of high school students made a suicide attempt. Suicide doesn't just affect a certain kind of person – it can affect anyone.

If you do see signs of suicide in your teen, says Dr. Hoover, ask directly if he or she is considering suicide and whether he or she has made a specific plan and has done anything to carry it out. Then get professional help immediately. Take the teen to a doctor, psychologist, therapist or community mental health center for a formal mental health assessment.

You can also take the teen to an emergency room (or call 9-1-1) if they are an immediate danger to him/herself or others. In addition, you can call a helpline like The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for more help on what to do next.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 is staffed by professionals who are available to speak with you 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

APA Reference

Tracy, N.

(2022, January 11). Teen Suicide Warning Signs: What Parents Should Look For, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, November 10 from https://www.healthyplace.com/suicide/teen-suicide-warning-signs-what-parents-should-look-for

Dealing with Anger and Guilt After A Suicide

After the suicide of a loved one or friend, you may feel shock, disbelief and, yes, anger. What is that about?

After losing a loved one to suicide, it isn't uncommon to struggle with conflicting feelings of anger and grief.

-

Know that it's normal to feel anger towards the loved one who committed suicide at the same time that you feel overwhelming grief over their loss. They made a devastating choice that will impact the rest of your life, leaving you to pick up the pieces and deal with the aftermath.

-

It's also normal to feel guilty after catching yourself feeling anger toward the deceased.

-

As yourself whether you love or hate the person you lost. Do you miss him/her or are you glad he/she is gone? Of course, you love and miss him/her. That's because these emotions are based on who your loved one was.

-

Do you feel guilty about loving and missing your loved one? Of course not. What you feel guilty about is your anger. The question is, are you angry at the person who committed suicide or are you angry about the choice he/she made to end his/her life, leaving you behind with the legacy of pain and hurt?

-

Chances are, you are angry at the choice, not the person - and it was your loved one who made that choice, not you. Had you known that he/she was going to commit suicide and known when/where you would have done what you could to stop it.

-

Accept that you couldn't change what happened and did the best you could with what you knew at the time. If you are burdening yourself with misplaced guilt, you are in effect confining yourself to an emotional prison.

-

The bars of an emotional prison are made out of guilt, anger, bitterness and resentment. But what people don't understand is that that kind of prison locks from the inside. There isn't anybody that can let you out of that prison except for you.

-

You wake up every morning and choose what to think. If you have chosen to carry the burden of guilt, shame, anger and hurt everywhere you go, what would happen if you decided, "I can't change what happened, so I better accept it and recognize that the life that I have today, tomorrow and the next day is going to be a function of what I choose?"

-

Give yourself permission to say, "It's okay to be mad at what he/she did." Because it was not okay. Then get back in the game. That's the bottom line. You experienced a devastating loss, but you didn't choose it. Give yourself permission to move on.

Source: Dr. Phil

APA Reference

Tracy, N.

(2022, January 11). Dealing with Anger and Guilt After A Suicide, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, November 10 from https://www.healthyplace.com/bipolar-disorder/articles/dealing-with-anger-and-guilt-after-a-suicide

What Does an ADHD Reward System Have to Do with Discipline?

An ADHD reward system is a vital component of discipline and behavior modification for kids with ADHD. Reward systems are purposeful ways to catch kids doing things right when their ADHD often causes them to do wrong. More than randomly giving a kid a prize for this or that, an ADHD reward system is organized and methodical, and it’s designed to increase desirable behavior. When a reward system plays an integral role in your discipline approach for your child with ADHD, you just might discover that your child is learning how to cooperate and get along.

Myths About Using an ADHD Reward System for Discipline

Even though using rewards for disciplining kids with ADHD has been shown to be effective, there is still some uncertainty about the idea of disciplining by rewarding kids. Some common myths:

- Using such a system is wrong because it rewards kids for doing what they are expected to do.

- Rewards teach kids to do good only to get something in return.

- An ADHD rewards system teaches kids to be manipulative by being good when they want something and then returning to disruptive and defiant behavior…until the next time they want something.

Let’s be myth-busters and debunk these untruths.

Why an ADHD Reward System is Necessary and Effective

Kids with ADHD don’t misbehave on purpose. They are impulsive, hyperactive, and have difficulties listening and focusing because of executive functioning issues in the brain. An ADHD reward system is a teaching tool with a positive outcome. (Discipline, after all, means “to teach.”)

- For kids with ADHD, rewards help them learn, remember, and do what’s expected of them.

- An ADHD rewards system teaches kids that they can behave well.

- Rewards help these kids understand the connections between their behavior and an outcome.

- Kids with ADHD have to work harder than many other kids to behave correctly. Rewarding them acknowledges their hard work.

- Rewards help kids develop the ability to override their brain’s executive functioning problems.

An ADHD rewards system makes a positive impact on kids and their behavior, but how do you use it?

How to Discipline a Child with an ADHD Reward System

Rewards are a component of behavior modification, a widely used discipline technique for kids with ADHD. Behavior modification, or behavior therapy, uses clear and understandable rules, consequences for not following them, and rewards for following them. The rewards aspect of discipline can be fun and light-hearted, a welcome relief from the stress that can accompany behavior and discipline.

A token economy is the primary component of a reward system. In a token economy, kids earn small items that they save to buy a bigger reward. Some parents use a jar and give their child marbles, pebbles from a craft store, plastic coins, or other small tokens. Kids put their earnings in the jar and watch as it fills. When the jar is full (it shouldn’t be too big), the child has earned a bigger reward, one that is clear ahead of time.

Some parents use sticker charts rather than a jar, but the principle is the same. A child receives stickers for good behavior and earns a larger reward when the chart is complete.

Another aspect of the reward system is immediate, positive reinforcement. Catch your child being good, and reinforce their behavior with verbal praise, a hug, a surprise treat—anything that alerts your child to the fact that they’re on track and you appreciate it.

Rewards don’t have to be huge or expensive. They should be simple and appealing to your child. They are most effective when kids have a say into what they will earn. Some families use rewards such as:

- Time to spend with a friend

- One-on-one time with a parent

- A special treat like going out for ice cream

- Choosing a family meal

- Extra playtime before bed

- Extra TV time or time for videogames

- A fun activity

An ADHD reward system has advantages beyond shaping behavior.

Advantages of Using an ADHD Reward System as Part of Discipline

Rewarding your child as part of teaching them behavior and skills like organization offers many advantages. It works so well for kids with ADHD because rewards:

- Are concrete; with a token economy, kids see their progress

- Motivate; kids want to do well

- Improve impulse control as kids progress from wanting instant gratification to waiting to earn a bigger reward

- Boost self-efficacy, that proud sense of “I did it!”

An ADHD reward system is an important part of discipline. With a reward system you teach your child what to do and how to build life skills.

See Also:

APA Reference

Peterson, T.

(2022, January 11). What Does an ADHD Reward System Have to Do with Discipline?, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, November 10 from https://www.healthyplace.com/parenting/discipline/what-does-an-adhd-reward-system-have-to-do-with-discipline

Suicide Prevention: Bipolar and Suicide

Many with bipolar disorder have suicidal thoughts. If you're in a suicidal depression, here are some suggestions. Also, how to prevent suicide over the long-term.

"Notwithstanding, all we have to live for, the brain in crisis has a perverse way of having us think the very opposite."

Bipolar disorder and depression kill. Simple. Some fifteen percent of us who suffer from major depression will die by our own hand. Many more than that will make the attempt. And many more still will die by "accident" or "slow suicide" through reckless behavior or personal abuse and neglect.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, suicide is the 9th leading cause of death in the US (more than 30,000 a year). Women will make the most attempts, but men will be by far more successful, by a margin of four to one. In teens and young adults, suicide is the 3rd leading cause of death, after accidents and homicides, more than all natural diseases combined.

Suicidal depression does not discriminate. It affects both the strong and the weak, the rich and the poor. War heroes have been taken down. So have survivors of the Nazi death camps. As have successful business people and artists and mothers and those with everything to live for.

We are talking epidemic numbers. At any given moment, five percent of the general population is suffering from a major depressive episode. Over the course of a lifetime, major depression will strike 20% of the population, numbers comparable to cancer and heart disease.

We are talking battlefield odds. Those with major depression have an 85% survival rate, but the prospect of finding ourselves in the lucky majority brings us only small relief. The experience has exposed us to our worst vulnerabilities, and deep inside we no longer trust what tomorrow may bring. We may still be walking and breathing, but we have been as close inside death as this side of life permits, and our minds will never let us forget it.

We ponder the fates of the unlucky minority, and sometimes we say a prayer. We contemplate the tortures their brains exposed them to and know for a fact that no God would ever hold judgment against them. For the time being, we are the lucky ones, but tomorrow that may change.

Still, we do have a certain amount of control in managing tomorrow. We who have survived know what we are up against - and can plan accordingly. Following are some common sense guidelines:

Preventing suicide over the long term:

- Cultivate friends or family members you can call on should you find yourself in crisis. If you have no friends or family you can trust, then seek out a support group, live or online.

- About posting your cry for help on the Internet: choose your site or mailing list very carefully. If you are new and posting to a very busy list, your appeal may be lost in the shuffle. At the opposite end, your message may go completely unread on bulletin boards with little or no traffic. It may take a few weeks before you establish a presence on a particular list or board. By then, you will probably be on email or ICQ terms with some of the members.

- Look up the numbers of various local suicide hotlines and keep them where you can find them. Familiarize yourself with the Internet crisis and suicide sites and bookmark the ones you like.

- Establish a close relationship with your doctor or psychiatrist. Ask yourself: is this someone you can call on in the middle of the night? Or, if not, will someone be there to respond to your call?

- Remove all guns and rifles from your home. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 60% of all suicides are committed with a firearm. This is not an anti-NRA message. We're just being sensible, that's all.

- The same principle that applies to firearms applies in part to medications. The tricyclic and tetracyclic anti-depressants can be fatal in overdose. You may want to switch to a different anti-depressant if you don't trust yourself. If you must keep certain medicines in the house, it may be advisable to turn them over to a loved one.

- Watch your thoughts and feelings very carefully. You may be able to pick up subtle signals in your mind before a full-scale crisis overwhelms you. Actually visualizing the act should set off every warning bell.

In an Actual Crisis:

All too often, a suicidal depression catches us alone and off-guard. Notwithstanding all we have to live for and all those who care for us, the brain in crisis has a perverse way of having us think the very opposite. To those of you who are in this state right now:

- Promise yourself another 24 hours.

- Now call a trusted friend or loved one or a crisis hotline. Remember, there is no shame in reaching out.

- Your other option is calling your psychiatrist or getting yourself to the emergency room.

- Time is of the essence. Do not delay in seeking help.

- Be persistent. Do not be put off by the bad practices of some of the health system's gatekeepers. You are there to get help and you are there to get it NOW.

- Finally, take comfort in the fact that help is on the way. Your brain at the moment may not allow you to think hopeful thoughts. But it cannot keep out the knowledge that others are hoping on your behalf. This may be that precious one inch of life you can hold onto at the moment, the one that can eventually lead you to a tomorrow worth living.

About the author: John McManamy is diagnosed with bipolar disorder. He is an authority on the subject of bipolar having written a book and many articles on the subject. Click the link to purchase his book Living Well with Depression and Bipolar Disorder: What Your Doctor Doesn't Tell You...That You Need to Know.

APA Reference

Staff, H.

(2022, January 11). Suicide Prevention: Bipolar and Suicide, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, November 10 from https://www.healthyplace.com/bipolar-disorder/articles/suicide-prevention-bipolar-and-suicide