Women, Food and Eating Disorders

Making Peace with Food

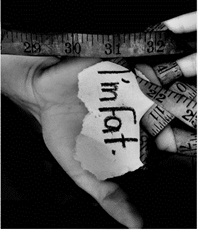

Women have related intimately with food since time began, as feeders and nurturers, harvesters, gatherers, and cooks. But in recent decades, this relationship has grown troubled. It can be said, in fact, that very few women today feel completely comfortable with food, eating, and the bodies their diets should nourish. Research has confirmed what any of us could have guessed - it actually is the norm in this country for women to be dissatisfied with their bodies, to worry about how much they eat, and to believe they should be dieting. What does this mean, and can we change it?

Women have related intimately with food since time began, as feeders and nurturers, harvesters, gatherers, and cooks. But in recent decades, this relationship has grown troubled. It can be said, in fact, that very few women today feel completely comfortable with food, eating, and the bodies their diets should nourish. Research has confirmed what any of us could have guessed - it actually is the norm in this country for women to be dissatisfied with their bodies, to worry about how much they eat, and to believe they should be dieting. What does this mean, and can we change it?

Thinking in the worst possible terms, this mindset implies that eating disorders, some of which are life-threatening and most of which are soul-torturing, are here to stay. Although the modern quest for thinness does not, in and of itself, automatically lead to eating disorders, dieting does precede most eating disorders. Consequently, this could also mean that the diet industry will continue to thrive while women who are not skinny will continue to feel depressed or inadequate.

Thinking a little more optimistically, we could anticipate an increasing awareness of the dangers posed by our diet-obsessed culture. More people could be alerted to the roots and results of ongoing body dissatisfaction and frequent dieting. In fact, such things are beginning to occur. Many individual women, however, continue to feel drained of at least some self-esteem and creative energy as a result of remaining fixed on the elusive goals of a perfect body and perfectly-regulated (never gluttonous) eating.

Understanding eating disorders as well as more "normal" kinds of unhappiness with eating and the body challenges us. These are complex matters that touch on our emotions, our physiology, our family histories, and our social and political context. This article lays a groundwork that will serve to help us achieve this understanding - and start, I hope, to help us make peace with food, our natural hungers, and the amazing bodies we are fortunate to possess.

I do not mean to exclude men from these discussions. I do, however, address these words to women directly, as women have much higher rates of eating disorders, as well as lesser forms of body dissatisfaction. Many men do suffer from similar ailments, though, and all are certainly invited to read, talk back in future chat rooms, and to ask their questions.

Defining Eating Disorders

People often wonder, when does "normal" dieting, or "normal" overeating, stop being normal and cross the line into an eating disorder? It is important to recognize that many, many people suffer from conflicted relationships with their eating. However, there are degrees of suffering and degrees of danger to health, with clinically diagnosable eating disorders inflicting the most of each. Eating disorders assume a few different forms.

Anorexia Nervosa is a condition in which a person literally starves the body of the nutrients it needs. People with anorexia often claim they are not hungry, strive to eat very little (even to the point of counting out flakes of cereal or individual grapes), and have an exaggerated, irrational fear of becoming fat. The fear of fat exists despite actual body size; in fact, the person afflicted may be very skinny or even skeletal. To be diagnosed with anorexia, one must be 15% below normal weight.

Anorexia Nervosa is a condition in which a person literally starves the body of the nutrients it needs. People with anorexia often claim they are not hungry, strive to eat very little (even to the point of counting out flakes of cereal or individual grapes), and have an exaggerated, irrational fear of becoming fat. The fear of fat exists despite actual body size; in fact, the person afflicted may be very skinny or even skeletal. To be diagnosed with anorexia, one must be 15% below normal weight.

Common behaviors include denial of how serious the condition is, secretiveness about how much has been eaten, the wearing of baggy clothes to hide thinness, avoidance of social events where food will be present, and obsessions with cooking or feeding food to others. In women, menstruation stops. Physical symptoms can include hair loss, skin dryness, temperature deregulation (feeling cold all the time), brittle nails, sleeplessness, hyperactivity, the development of obsessions, and the development of soft, baby-like hair on the body called "lanuga." Some people who self-starve will occasionally binge eat and then get rid of the "damage" by purging or overexercising. People who are underweight and undereating to the point of anorexia also distort information and perception (as part of the disorder, not necessarily on purpose), so that no amount of "talking sense" - listing health dangers, noting the person's boniness - seems to make a difference.

Bulimia Nervosa refers to the condition in which large quantities of food are consumed in a way that feels out-of-control and is not normal for the situation (for instance, eating a lot at Thanksgiving is not necessarily binging). The food binge can consist of thousands of calories, most often carbohydrates and fats. The person ingesting all this food then tries to get rid of it by vomiting, overexercising, taking laxatives, or some other means. A person with bulimia can be normal, below normal, or overweight. Menstruation does not necessarily stop, although it can.

Eating is usually done in isolation, and the individual often feels very ashamed and out-of-control with this behavior. Like an addictive substance, however, the food binge is often looked forward to and protected by the person as a source of short-term relief or good feelings. People with bulimia usually fear getting fat, as in anorexia. They can develop dental problems, throat irritations, swelling around the base of the jaw, lesions in the esophagus, gastrointestinal problems, and heart problems (including heart emergencies) from electrolyte imbalance or the use of Ipecac to induce vomiting.

Binge eating disorder involves eating in quantities similar to bulimia, but the purging afterward does not occur. People with binge eating disorder are more likely to be overweight than those with bulimia, but are not always so. Health problems are usually fewer than those found in the other eating disorders, although individuals can be at risk for those conditions associated with high calorie and fat intake generally.

Less common forms of clinical eating disorder involve variations on the themes already discussed. For example, some people purge what they eat even if it wasn't a binge or large amount of food. Some people develop the behaviors and thinking of the anorexic, but may be overweight or may not have stopped menstruating.

While all of the eating disorders carry health risks, anorexia has the highest mortality rate and the highest risk of sudden death (from electrolyte imbalance or bradycardia, an unusually low heart rate). Anorexia is less common than bulimia and most often afflicts women beginning at age 13 through the early 20s. People usually develop bulimia somewhat later, around age 15 or 16 through the early 30s. Men, as well as women who are older or younger than these ages, can also develop these syndromes.

I hope this article will help people to begin thinking about their own relationships with food and how they might like to change them. Your questions and comments are, of course, always welcomed.

next: Persistent Perfectionists: The Idea of Perfection Remains Even After Eating Disorders Treatment

~ eating disorders library

~ all articles on eating disorders

APA Reference

Gluck, S.

(2008, November 22). Women, Food and Eating Disorders, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2026, January 30 from https://www.healthyplace.com/eating-disorders/articles/women-food-and-eating-disorders