Lantus for Treatment of Diabetes - Lantus Full Prescribing Information

Brand Name: Lantus

Generic Name: insulin glargine

Dosage Form: Injection (Lantus must NOT be diluted or mixed with any other insulin or solution)

Contents:

Description

Clinical Pharmacology

Indications and Usage

Contraindications

Warnings

Precautions

Adverse Reactions

Dosage and Administration

How is Supplied

Lantus, insulin glargine (rDNA origin), patient information (in plain English)

Description

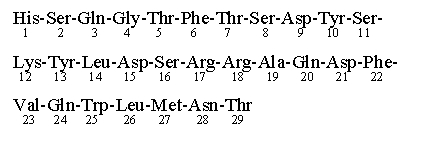

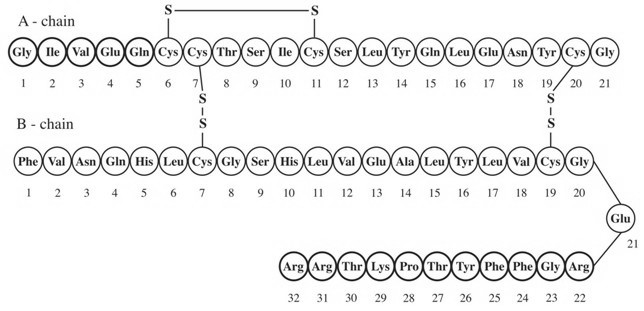

Lantus® (insulin glargine [rDNA origin] injection) is a sterile solution of insulin glargine for use as an injection. Insulin glargine is a recombinant human insulin analog that is a long-acting (up to 24-hour duration of action), parenteral blood-glucose-lowering agent. (See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY). Lantus is produced by recombinant DNA technology utilizing a non-pathogenic laboratory strain of Escherichia coli (K12) as the production organism. Insulin glargine differs from human insulin in that the amino acid asparagine at position A21 is replaced by glycine and two arginines are added to the C-terminus of the B-chain. Chemically, it is 21A-Gly-30Ba-L-Arg-30Bb-L-Arg-human insulin and has the empirical formula C267H404N72O78S6 and a molecular weight of 6063. It has the following structural formula:

Lantus consists of insulin glargine dissolved in a clear aqueous fluid. Each milliliter of Lantus (insulin glargine injection) contains 100 IU (3.6378 mg) insulin glargine.

Inactive ingredients for the 10 mL vial are 30 mcg zinc, 2.7 mg m-cresol, 20 mg glycerol 85%, 20 mcg polysorbate 20, and water for injection.

Inactive ingredients for the 3 mL cartridge are 30 mcg zinc, 2.7 mg m-cresol, 20 mg glycerol 85%, and water for injection.

The pH is adjusted by addition of aqueous solutions of hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide. Lantus has a pH of approximately 4.

Clinical Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action

The primary activity of insulin, including insulin glargine, is regulation of glucose metabolism. Insulin and its analogs lower blood glucose levels by stimulating peripheral glucose uptake, especially by skeletal muscle and fat, and by inhibiting hepatic glucose production. Insulin inhibits lipolysis in the adipocyte, inhibits proteolysis, and enhances protein synthesis.

Pharmacodynamics

Insulin glargine is a human insulin analog that has been designed to have low aqueous solubility at neutral pH. At pH 4, as in the Lantus injection solution, it is completely soluble. After injection into the subcutaneous tissue, the acidic solution is neutralized, leading to formation of microprecipitates from which small amounts of insulin glargine are slowly released, resulting in a relatively constant concentration/time profile over 24 hours with no pronounced peak. This profile allows once-daily dosing as a patient's basal insulin.

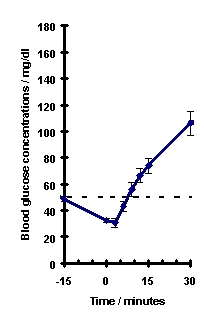

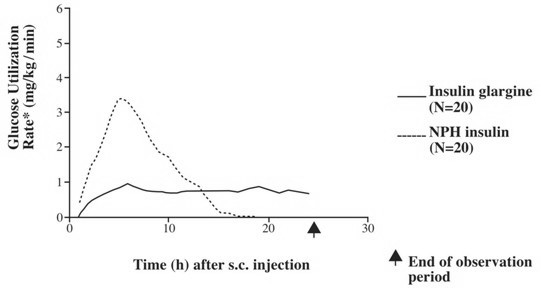

In clinical studies, the glucose-lowering effect on a molar basis (i.e., when given at the same doses) of intravenous insulin glargine is approximately the same as human insulin. In euglycemic clamp studies in healthy subjects or in patients with type 1 diabetes, the onset of action of subcutaneous insulin glargine was slower than NPH human insulin. The effect profile of insulin glargine was relatively constant with no pronounced peak and the duration of its effect was prolonged compared to NPH human insulin. Figure 1 shows results from a study in patients with type 1 diabetes conducted for a maximum of 24 hours after the injection. The median time between injection and the end of pharmacological effect was 14.5 hours (range: 9.5 to 19.3 hours) for NPH human insulin, and 24 hours (range: 10.8 to >24.0 hours) (24 hours was the end of the observation period) for insulin glargine.

Figure 1. Activity Profile in Patients with Type 1 Diabetesâ€

*Determined as amount of glucose infused to maintain constant plasma glucose levels (hourly mean values); indicative of insulin activity.

†Between-patient variability (CV, coefficient of variation); insulin glargine, 84% and NPH, 78%.

The longer duration of action (up to 24 hours) of Lantus is directly related to its slower rate of absorption and supports once-daily subcutaneous administration. The time course of action of insulins, including Lantus, may vary between individuals and/or within the same individual.

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption and Bioavailability

After subcutaneous injection of insulin glargine in healthy subjects and in patients with diabetes, the insulin serum concentrations indicated a slower, more prolonged absorption and a relatively constant concentration/time profile over 24 hours with no pronounced peak in comparison to NPH human insulin. Serum insulin concentrations were thus consistent with the time profile of the pharmacodynamic activity of insulin glargine.

After subcutaneous injection of 0.3 IU/kg insulin glargine in patients with type 1 diabetes, a relatively constant concentration/time profile has been demonstrated. The duration of action after abdominal, deltoid, or thigh subcutaneous administration was similar.

Metabolism

A metabolism study in humans indicates that insulin glargine is partly metabolized at the carboxyl terminus of the B chain in the subcutaneous depot to form two active metabolites with in vitro activity similar to that of insulin, M1 (21A-Gly-insulin) and M2 (21A-Gly-des-30B-Thr-insulin). Unchanged drug and these degradation products are also present in the circulation.

Special Populations

Age, Race, and Gender

Information on the effect of age, race, and gender on the pharmacokinetics of Lantus is not available. However, in controlled clinical trials in adults (n=3890) and a controlled clinical trial in pediatric patients (n=349), subgroup analyses based on age, race, and gender did not show differences in safety and efficacy between insulin glargine and NPH human insulin.

Smoking

The effect of smoking on the pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of Lantus has not been studied.

Pregnancy

The effect of pregnancy on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Lantus has not been studied (see PRECAUTIONS, Pregnancy).

Obesity

In controlled clinical trials, which included patients with Body Mass Index (BMI) up to and including 49.6 kg/m2, subgroup analyses based on BMI did not show any differences in safety and efficacy between insulin glargine and NPH human insulin.

Renal Impairment

The effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of Lantus has not been studied. However, some studies with human insulin have shown increased circulating levels of insulin in patients with renal failure. Careful glucose monitoring and dose adjustments of insulin, including Lantus, may be necessary in patients with renal dysfunction (see PRECAUTIONS, Renal Impairment).

Hepatic Impairment

The effect of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of Lantus has not been studied. However, some studies with human insulin have shown increased circulating levels of insulin in patients with liver failure. Careful glucose monitoring and dose adjustments of insulin, including Lantus, may be necessary in patients with hepatic dysfunction (see PRECAUTIONS, Hepatic Impairment).

Clinical Studies

The safety and effectiveness of insulin glargine given once-daily at bedtime was compared to that of once-daily and twice-daily NPH human insulin in open-label, randomized, active-control, parallel studies of 2327 adult patients and 349 pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and 1563 adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (see Tables 1-3). In general, the reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) with Lantus was similar to that with NPH human insulin. The overall rates of hypoglycemia did not differ between patients with diabetes treated to Lantus compared with NPH human insulin.

Type 1 Diabetes-Adult (see Table 1).

In two large, randomized, controlled clinical studies (Studies A and B), patients with type 1 diabetes (Study A; n=585, Study B; n=534) were randomized to basal-bolus treatment with Lantus once daily at bedtime or to NPH human insulin once or twice daily and treated for 28 weeks. Regular human insulin was administered before each meal. Lantus was administered at bedtime. NPH human insulin was administered once daily at bedtime or in the morning and at bedtime when used twice daily. In one large, randomized, controlled clinical study (Study C), patients with type 1 diabetes (n=619) were treated for 16 weeks with a basal-bolus insulin regimen where insulin lispro was used before each meal. Lantus was administered once daily at bedtime and NPH human insulin was administered once or twice daily. In these studies, Lantus and NPH human insulin had a similar effect on glycohemoglobin with a similar overall rate of hypoglycemia.

Table 1: Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus-Adult

| Study A | Study B | Study C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration | 28 weeks | 28 weeks | 16 weeks | |||

| Treatment in combination with | Regular insulin | Regular insulin | Insulin lispro | |||

| Lantus | NPH | Lantus | NPH | Lantus | NPH | |

| Number of subjects treated | 292 | 293 | 264 | 270 | 310 | 309 |

| HbA1c | ||||||

| Endstudy mean | 8.13 | 8.07 | 7.55 | 7.49 | 7.53 | 7.60 |

| Adj. mean change from baseline | +0.21 | +0.10 | -0.16 | -0.21 | -0.07 | -0.08 |

| Lantus - NPH | +0.11 | +0.05 | +0.01 | |||

| 95% CI for Treatment difference | (-0.03; +0.24) | (-0.08; +0.19) | (-0.11; +0.13) | |||

| Basal insulin dose | ||||||

| Endstudy mean | 19.2 | 22.8 | 24.8 | 31.3 | 23.9 | 29.2 |

| Mean change from baseline | -1.7 | -0.3 | -4.1 | +1.8 | -4.5 | +0.9 |

| Total insulin dose | ||||||

| Endstudy mean | 46.7 | 51.7 | 50.3 | 54.8 | 47.4 | 50.7 |

| Mean change from baseline | -1.1 | -0.1 | +0.3 | +3.7 | -2.9 | +0.3 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Endstudy mean | 146.3 | 150.8 | 147.8 | 154.4 | 144.4 | 161.3 |

| Adj. mean change from baseline | -21.1 | -16.0 | -20.2 | -16.9 | -29.3 | -11.9 |

Type 1 Diabetes-Pediatric (see Table 2).

In a randomized, controlled clinical study (Study D), pediatric patients (age range 6 to 15 years) with type 1 diabetes (n=349) were treated for 28 weeks with a basal-bolus insulin regimen where regular human insulin was used before each meal. Lantus was administered once daily at bedtime and NPH human insulin was administered once or twice daily. Similar effects on glycohemoglobin and the incidence of hypoglycemia were observed in both treatment groups.

Table 2: Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus-Pediatric

| Study D | ||

|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration | 28 weeks | |

| Treatment in combination with | Regular insulin | |

| Lantus | NPH | |

| Number of subjects treated | 174 | 175 |

| HbA1c | ||

| Endstudy mean | 8.91 | 9.18 |

| Adj. mean change from baseline | +0.28 | +0.27 |

| Lantus - NPH | +0.01 | |

| 95% CI for Treatment difference | (-0.24; +0.26) | |

| Basal insulin dose | ||

| Endstudy mean | 18.2 | 21.1 |

| Mean change from baseline | -1.3 | +2.4 |

| Total insulin dose | ||

| Endstudy mean | 45.0 | 46.0 |

| Mean change from baseline | +1.9 | +3.4 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | ||

| Endstudy mean | 171.9 | 182.7 |

| Adj. mean change from baseline | -23.2 | -12.2 |

Type 2 Diabetes-Adult (see Table 3).

In a large, randomized, controlled clinical study (Study E) (n=570), Lantus was evaluated for 52 weeks as part of a regimen of combination therapy with insulin and oral antidiabetes agents (a sulfonylurea, metformin, acarbose, or combinations of these drugs). Lantus administered once daily at bedtime was as effective as NPH human insulin administered once daily at bedtime in reducing glycohemoglobin and fasting glucose. There was a low rate of hypoglycemia that was similar in Lantus and NPH human insulin treated patients. In a large, randomized, controlled clinical study (Study F), in patients with type 2 diabetes not using oral antidiabetes agents (n=518), a basal-bolus regimen of Lantus once daily at bedtime or NPH human insulin administered once or twice daily was evaluated for 28 weeks. Regular human insulin was used before meals as needed. Lantus had similar effectiveness as either once- or twice-daily NPH human insulin in reducing glycohemoglobin and fasting glucose with a similar incidence of hypoglycemia.

Table 3: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-Adult

| Study E | Study F | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration | 52 weeks | 28 weeks | ||

| Treatment in combination with | Oral agents | Regular insulin | ||

| Lantus | NPH | Lantus | NPH | |

| Number of subjects treated | 289 | 281 | 259 | 259 |

| HbA1c | ||||

| Endstudy mean | 8.51 | 8.47 | 8.14 | 7.96 |

| Adj. mean change from baseline | -0.46 | -0.38 | -0.41 | -0.59 |

| Lantus - NPH | -0.08 | +0.17 | ||

| 95% CI for Treatment difference | (-0.28; +0.12) | (-0.00; +0.35) | ||

| Basal insulin dose | ||||

| Endstudy mean | 25.9 | 23.6 | 42.9 | 52.5 |

| Mean change from baseline | +11.5 | +9.0 | -1.2 | +7.0 |

| Total insulin dose | ||||

| Endstudy mean | 25.9 | 23.6 | 74.3 | 80.0 |

| Mean change from baseline | +11.5 | +9.0 | +10.0 | +13.1 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | ||||

| Endstudy mean | 126.9 | 129.4 | 141.5 | 144.5 |

| Adj. mean change from baseline | -49.0 | -46.3 | -23.8 | -21.6 |

Lantus Flexible Daily Dosing

The safety and efficacy of Lantus administered pre-breakfast, pre-dinner, or at bedtime were evaluated in a large, randomized, controlled clinical study, in patients with type 1 diabetes (study G, n=378). Patients were also treated with insulin lispro at mealtime. Lantus administered at different times of the day resulted in similar reductions in glycated hemoglobin compared to that with bedtime administration (see Table 4). In these patients, data are available from 8-point home glucose monitoring. The maximum mean blood glucose level was observed just prior to injection of Lantus regardless of time of administration, i.e. pre-breakfast, pre-dinner, or bedtime.

In this study, 5% of patients in the Lantus-breakfast arm discontinued treatment because of lack of efficacy. No patients in the other two arms discontinued for this reason. Routine monitoring during this trial revealed the following mean changes in systolic blood pressure: pre-breakfast group, 1.9 mm Hg; pre-dinner group, 0.7 mm Hg; pre-bedtime group, -2.0 mm Hg.

The safety and efficacy of Lantus administered pre-breakfast or at bedtime were also evaluated in a large, randomized, active-controlled clinical study (Study H, n=697) in type 2 diabetes patients no longer adequately controlled on oral agent therapy. All patients in this study also received AMARYL® (glimepiride) 3 mg daily. Lantus given before breakfast was at least as effective in lowering glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) as Lantus given at bedtime or NPH human insulin given at bedtime (see Table 4).

Table 4: Flexible Lantus Daily Dosing in Type 1 (Study G) and Type 2 (Study H) Diabetes Mellitus

| Study G | Study H | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatmentduration | 24 weeks | 24 weeks | ||||

| Treatment in combination with: | Insulin lispro | AMARYL® (glimepiride) | ||||

| Lantus Breakfast | Lantus Dinner | Lantus Bedtime | Lantus Breakfast | Lantus Bedtime | NPH Bedtime | |

| ||||||

| Number of subjects treated* | 112 | 124 | 128 | 234 | 226 | 227 |

| HbA1c | ||||||

| Baseline mean | 7.56 | 7.53 | 7.61 | 9.13 | 9.07 | 9.09 |

| Endstudy mean | 7.39 | 7.42 | 7.57 | 7.87 | 8.12 | 8.27 |

| Mean change from baseline | -0.17 | -0.11 | -0.04 | -1.26 | -0.95 | -0.83 |

| Basal insulin dose (IU) | ||||||

| Endstudy mean | 27.3 | 24.6 | 22.8 | 40.4 | 38.5 | 36.8 |

| Mean change from baseline | 5.0 | 1.8 | 1.5 | |||

| Total insulin dose (IU) | NA†| NA | NA | |||

| Endstudy mean | 53.3 | 54.7 | 51.5 | |||

| Mean change from baseline | 1.6 | 3.0 | 2.3 | |||

Indications and Usage

Lantus is indicated for once-daily subcutaneous administration for the treatment of adult and pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus or adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who require basal (long-acting) insulin for the control of hyperglycemia.

Contraindications

Lantus is contraindicated in patients hypersensitive to insulin glargine or the excipients.

Warnings

Hypoglycemia is the most common adverse effect of insulin, including Lantus. As with all insulins, the timing of hypoglycemia may differ among various insulin formulations. Glucose monitoring is recommended for all patients with diabetes.

Any change of insulin should be made cautiously and only under medical supervision. Changes in insulin strength, timing of dosing, manufacturer, type (e.g., regular, NPH, or insulin analogs), species (animal, human), or method of manufacture (recombinant DNA versus animal-source insulin) may result in the need for a change in dosage. Concomitant oral antidiabetes treatment may need to be adjusted.

Precautions

General

Lantus is not intended for intravenous administration. The prolonged duration of activity of insulin glargine is dependent on injection into subcutaneous tissue. Intravenous administration of the usual subcutaneous dose could result in severe hypoglycemia.

Lantus must NOT be diluted or mixed with any other insulin or solution. If Lantus is diluted or mixed, the solution may become cloudy, and the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile (e.g., onset of action, time to peak effect) of Lantus and/or the mixed insulin may be altered in an unpredictable manner. When Lantus and regular human insulin were mixed immediately before injection in dogs, a delayed onset of action and time to maximum effect for regular human insulin was observed. The total bioavailability of the mixture was also slightly decreased compared to separate injections of Lantus and regular human insulin. The relevance of these observations in dogs to humans is not known.

As with all insulin preparations, the time course of Lantus action may vary in different individuals or at different times in the same individual and the rate of absorption is dependent on blood supply, temperature, and physical activity.

Insulin may cause sodium retention and edema, particularly if previously poor metabolic control is improved by intensified insulin therapy.

Hypoglycemia

As with all insulin preparations, hypoglycemic reactions may be associated with the administration of Lantus. Hypoglycemia is the most common adverse effect of insulins. Early warning symptoms of hypoglycemia may be different or less pronounced under certain conditions, such as long duration of diabetes, diabetes nerve disease, use of medications such as beta-blockers, or intensified diabetes control (see PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions). Such situations may result in severe hypoglycemia (and, possibly, loss of consciousness) prior to patients' awareness of hypoglycemia.

The time of occurrence of hypoglycemia depends on the action profile of the insulins used and may, therefore, change when the treatment regimen or timing of dosing is changed. Patients being switched from twice daily NPH insulin to once-daily Lantus should have their initial Lantus dose reduced by 20% from the previous total daily NPH dose to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION, Changeover to Lantus).

The prolonged effect of subcutaneous Lantus may delay recovery from hypoglycemia.

In a clinical study, symptoms of hypoglycemia or counterregulatory hormone responses were similar after intravenous insulin glargine and regular human insulin both in healthy subjects and patients with type 1 diabetes.

Renal Impairment

Although studies have not been performed in patients with diabetes and renal impairment, Lantus requirements may be diminished because of reduced insulin metabolism, similar to observations found with other insulins (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Special Populations).

Hepatic Impairment

Although studies have not been performed in patients with diabetes and hepatic impairment, Lantus requirements may be diminished due to reduced capacity for gluconeogenesis and reduced insulin metabolism, similar to observations found with other insulins (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Special Populations).

Injection Site and Allergic Reactions

As with any insulin therapy, lipodystrophy may occur at the injection site and delay insulin absorption. Other injection site reactions with insulin therapy include redness, pain, itching, hives, swelling, and inflammation. Continuous rotation of the injection site within a given area may help to reduce or prevent these reactions. Most minor reactions to insulins usually resolve in a few days to a few weeks.

Reports of injection site pain were more frequent with Lantus than NPH human insulin (2.7% insulin glargine versus 0.7% NPH). The reports of pain at the injection site were usually mild and did not result in discontinuation of therapy.

Immediate-type allergic reactions are rare. Such reactions to insulin (including insulin glargine) or the excipients may, for example, be associated with generalized skin reactions, angioedema, bronchospasm, hypotension, or shock and may be life threatening.

Intercurrent Conditions

Insulin requirements may be altered during intercurrent conditions such as illness, emotional disturbances, or stress.

Information for Patients

Lantus must only be used if the solution is clear and colorless with no particles visible (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION, Preparation and Handling).

Patients must be advised that Lantus must NOT be diluted or mixed with any other insulin or solution (see PRECAUTIONS, General).

Patients should be instructed on self-management procedures including glucose monitoring, proper injection technique, and hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia management. Patients must be instructed on handling of special situations such as intercurrent conditions (illness, stress, or emotional disturbances), an inadequate or skipped insulin dose, inadvertent administration of an increased insulin dose, inadequate food intake, or skipped meals. Refer patients to the Lantus "Patient Information" circular for additional information.

As with all patients who have diabetes, the ability to concentrate and/or react may be impaired as a result of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia.

Patients with diabetes should be advised to inform their health care professional if they are pregnant or are contemplating pregnancy.

Drug Interactions

A number of substances affect glucose metabolism and may require insulin dose adjustment and particularly close monitoring.

The following are examples of substances that may increase the blood-glucose-lowering effect and susceptibility to hypoglycemia: oral antidiabetes products, ACE inhibitors, disopyramide, fibrates, fluoxetine, MAO inhibitors, propoxyphene, salicylates, somatostatin analog (e.g., octreotide), sulfonamide antibiotics.

The following are examples of substances that may reduce the blood-glucose-lowering effect of insulin: corticosteroids, danazol, diuretics, sympathomimetic agents (e.g., epinephrine, albuterol, terbutaline), isoniazid, phenothiazine derivatives, somatropin, thyroid hormones, estrogens, progestogens (e.g., in oral contraceptives), protease inhibitors and atypical antipsychotic medications (e.g. olanzapine and clozapine).

Beta-blockers, clonidine, lithium salts, and alcohol may either potentiate or weaken the blood-glucose-lowering effect of insulin. Pentamidine may cause hypoglycemia, which may sometimes be followed by hyperglycemia.

In addition, under the influence of sympatholytic medicinal products such as beta-blockers, clonidine, guanethidine, and reserpine, the signs of hypoglycemia may be reduced or absent.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

In mice and rats, standard two-year carcinogenicity studies with insulin glargine were performed at doses up to 0.455 mg/kg, which is for the rat approximately 10 times and for the mouse approximately 5 times the recommended human subcutaneous starting dose of 10 IU (0.008 mg/kg/day), based on mg/m2. The findings in female mice were not conclusive due to excessive mortality in all dose groups during the study. Histiocytomas were found at injection sites in male rats (statistically significant) and male mice (not statistically significant) in acid vehicle containing groups. These tumors were not found in female animals, in saline control, or insulin comparator groups using a different vehicle. The relevance of these findings to humans is unknown.

Insulin glargine was not mutagenic in tests for detection of gene mutations in bacteria and mammalian cells (Ames- and HGPRT-test) and in tests for detection of chromosomal aberrations (cytogenetics in vitro in V79 cells and in vivo in Chinese hamsters).

In a combined fertility and prenatal and postnatal study in male and female rats at subcutaneous doses up to 0.36 mg/kg/day, which is approximately 7 times the recommended human subcutaneous starting dose of 10 IU (0.008 mg/kg/day), based on mg/m2, maternal toxicity due to dose-dependent hypoglycemia, including some deaths, was observed. Consequently, a reduction of the rearing rate occurred in the high-dose group only. Similar effects were observed with NPH human insulin.

Pregnancy

Teratogenic Effects

Pregnancy Category C. Subcutaneous reproduction and teratology studies have been performed with insulin glargine and regular human insulin in rats and Himalayan rabbits. The drug was given to female rats before mating, during mating, and throughout pregnancy at doses up to 0.36 mg/kg/day, which is approximately 7 times the recommended human subcutaneous starting dose of 10 IU (0.008 mg/kg/day), based on mg/m2. In rabbits, doses of 0.072 mg/kg/day, which is approximately 2 times the recommended human subcutaneous starting dose of 10 IU (0.008 mg/kg/day), based on mg/m2, were administered during organogenesis. The effects of insulin glargine did not generally differ from those observed with regular human insulin in rats or rabbits. However, in rabbits, five fetuses from two litters of the high-dose group exhibited dilation of the cerebral ventricles. Fertility and early embryonic development appeared normal.

There are no well-controlled clinical studies of the use of insulin glargine in pregnant women. It is essential for patients with diabetes or a history of gestational diabetes to maintain good metabolic control before conception and throughout pregnancy. Insulin requirements may decrease during the first trimester, generally increase during the second and third trimesters, and rapidly decline after delivery. Careful monitoring of glucose control is essential in such patients. Because animal reproduction studies are not always predictive of human response, this drug should be used during pregnancy only if clearly needed.

Nursing Mothers

It is unknown whether insulin glargine is excreted in significant amounts in human milk. Many drugs, including human insulin, are excreted in human milk. For this reason, caution should be exercised when Lantus is administered to a nursing woman. Lactating women may require adjustments in insulin dose and diet.

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness of Lantus have been established in the age group 6 to 15 years with type 1 diabetes.

Geriatric Use

In controlled clinical studies comparing insulin glargine to NPH human insulin, 593 of 3890 patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes were 65 years and older. The only difference in safety or effectiveness in this subpopulation compared to the entire study population was an expected higher incidence of cardiovascular events in both insulin glargine and NPH human insulin-treated patients.

In elderly patients with diabetes, the initial dosing, dose increments, and maintenance dosage should be conservative to avoid hypoglycemic reactions. Hypoglycemia may be difficult to recognize in the elderly (see PRECAUTIONS, Hypoglycemia).

Adverse Reactions

The adverse events commonly associated with Lantus include the following:

Body as a whole: allergic reactions (see PRECAUTIONS).

Skin and appendages: injection site reaction, lipodystrophy, pruritus, rash (see PRECAUTIONS).

Other: hypoglycemia (see WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS).

In clinical studies in adult patients, there was a higher incidence of treatment-emergent injection site pain in Lantus-treated patients (2.7%) compared to NPH insulin-treated patients (0.7%). The reports of pain at the injection site were usually mild and did not result in discontinuation of therapy. Other treatment-emergent injection site reactions occurred at similar incidences with both insulin glargine and NPH human insulin.

Retinopathy was evaluated in the clinical studies by means of retinal adverse events reported and fundus photography. The numbers of retinal adverse events reported for Lantus and NPH treatment groups were similar for patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Progression of retinopathy was investigated by fundus photography using a grading protocol derived from the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS). In one clinical study involving patients with type 2 diabetes, a difference in the number of subjects with ≥3-step progression in ETDRS scale over a 6-month period was noted by fundus photography (7.5% in Lantus group versus 2.7% in NPH treated group). The overall relevance of this isolated finding cannot be determined due to the small number of patients involved, the short follow-up period, and the fact that this finding was not observed in other clinical studies.

Overdose

An excess of insulin relative to food intake, energy expenditure, or both may lead to severe and sometimes long-term and life-threatening hypoglycemia. Mild episodes of hypoglycemia can usually be treated with oral carbohydrates. Adjustments in drug dosage, meal patterns, or exercise may be needed.

More severe episodes with coma, seizure, or neurologic impairment may be treated with intramuscular/subcutaneous glucagon or concentrated intravenous glucose. After apparent clinical recovery from hypoglycemia, continued observation and additional carbohydrate intake may be necessary to avoid reoccurrence of hypoglycemia.

Dosage and Administration

Lantus is a recombinant human insulin analog. Its potency is approximately the same as human insulin. It exhibits a relatively constant glucose-lowering profile over 24 hours that permits once-daily dosing.

Lantus may be administered at any time during the day. Lantus should be administered subcutaneously once a day at the same time every day. For patients adjusting timing of dosing with Lantus, see WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS, Hypoglycemia. Lantus is not intended for intravenous administration (see PRECAUTIONS). Intravenous administration of the usual subcutaneous dose could result in severe hypoglycemia. The desired blood glucose levels as well as the doses and timing of antidiabetes medications must be determined individually. Blood glucose monitoring is recommended for all patients with diabetes. The prolonged duration of activity of Lantus is dependent on injection into subcutaneous space.

As with all insulins, injection sites within an injection area (abdomen, thigh, or deltoid) must be rotated from one injection to the next.

In clinical studies, there was no relevant difference in insulin glargine absorption after abdominal, deltoid, or thigh subcutaneous administration. As for all insulins, the rate of absorption, and consequently the onset and duration of action, may be affected by exercise and other variables.

Lantus is not the insulin of choice for the treatment of diabetes ketoacidosis. Intravenous short-acting insulin is the preferred treatment.

Pediatric Use

Lantus can be safely administered to pediatric patients ≥6 years of age. Administration to pediatric patients

Initiation of Lantus Therapy

In a clinical study with insulin naïve patients with type 2 diabetes already treated with oral antidiabetes drugs, Lantus was started at an average dose of 10 IU once daily, and subsequently adjusted according to the patient's need to a total daily dose ranging from 2 to 100 IU.

Changeover to Lantus

If changing from a treatment regimen with an intermediate- or long-acting insulin to a regimen with Lantus, the amount and timing of short-acting insulin or fast-acting insulin analog or the dose of any oral antidiabetes drug may need to be adjusted. In clinical studies, when patients were transferred from once-daily NPH human insulin or ultralente human insulin to once-daily Lantus, the initial dose was usually not changed. However, when patients were transferred from twice-daily NPH human insulin to Lantus once daily, to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia, the initial dose (IU) was usually reduced by approximately 20% (compared to total daily IU of NPH human insulin) and then adjusted based on patient response (see PRECAUTIONS, Hypoglycemia).

A program of close metabolic monitoring under medical supervision is recommended during transfer and in the initial weeks thereafter. The amount and timing of short-acting insulin or fast-acting insulin analog may need to be adjusted. This is particularly true for patients with acquired antibodies to human insulin needing high-insulin doses and occurs with all insulin analogs. Dose adjustment of Lantus and other insulins or oral antidiabetes drugs may be required; for example, if the patient's timing of dosing, weight or lifestyle changes, or other circumstances arise that increase susceptibility to hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia (see PRECAUTIONS, Hypoglycemia).

The dose may also have to be adjusted during intercurrent illness (see PRECAUTIONS, Intercurrent Conditions).

Preparation and Handling

Parenteral drug products should be inspected visually prior to administration whenever the solution and the container permit. Lantus must only be used if the solution is clear and colorless with no particles visible.

Mixing and diluting: Lantus must NOT be diluted or mixed with any other insulin or solution (see PRECAUTIONS, General).

Vial: The syringes must not contain any other medicinal product or residue.

Cartridge system: If OptiClik®, the Insulin Delivery Device for Lantus, malfunctions, Lantus may be drawn from the cartridge system into a U-100 syringe and injected.

How is Supplied

Lantus 100 units per mL (U-100) is available in the following package size:

10 mL vials (NDC 0088-2220-33)

3 mL cartridge system1, package of 5 (NDC 0088-2220-52)

1Cartridge systems are for use only in OptiClik® (Insulin Delivery Device)

Storage

Unopened Vial/Cartridge system

Unopened Lantus vials and cartridge systems should be stored in a refrigerator, 36°F - 46°F (2°C - 8°C). Lantus should not be stored in the freezer and it should not be allowed to freeze.

Discard if it has been frozen.

Open (In-Use) Vial/Cartridge system

Opened vials, whether or not refrigerated, must be used within 28 days after the first use. They must be discarded if not used within 28 days. If refrigeration is not possible, the open vial can be kept unrefrigerated for up to 28 days away from direct heat and light, as long as the temperature is not greater than 86°F (30°C).

The opened (in-use) cartridge system in OptiClik® should NOT be refrigerated but should be kept at room temperature (below 86°F [30°C]) away from direct heat and light. The opened (in-use) cartridge system in OptiClik® kept at room temperature must be discarded after 28 days. Do not store OptiClik®, with or without cartridge system, in a refrigerator at any time.

Lantus should not be stored in the freezer and it should not be allowed to freeze. Discard if it has been frozen.

These storage conditions are summarized in the following table:

| Not in-use (unopened) Refrigerated | Not in-use (unopened) Room Temperature | In-use (opened) (See Temperature Below) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mL Vial | Until expiration date | 28 days | 28 days Refrigerated or room temperature |

| 3 mL Cartridge system | Until expiration date | 28 days | 28 days Refrigerated or room temperature |

| 3 mL Cartridge system inserted into OptiClik® | 28 days Room temperature only (Do not refrigerate) |

Manufactured for an distributed by:

sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC

Bridgewater NJ 08807

Made in Germany

www.Lantus.com

© 2006 sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC

OptiClik® is a registered trademark of sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC, Bridgewater NJ 08807

last updated 04/2006

Lantus, insulin glargine (rDNA origin), patient information (in plain English)

Detailed Info on Signs, Symptoms, Causes, Treatments of Diabetes

The information in this monograph is not intended to cover all possible uses, directions, precautions, drug interactions or adverse effects. This information is generalized and is not intended as specific medical advice. If you have questions about the medicines you are taking or would like more information, check with your doctor, pharmacist, or nurse.

back to: Browse all Medications for Diabetes

APA Reference

Staff, H.

(2006, April 30). Lantus for Treatment of Diabetes - Lantus Full Prescribing Information, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2026, March 5 from https://www.healthyplace.com/diabetes/medications/lantus-glargine-insulin-treatment

Everyone feels anxious and under stress from time-to-time. Situations such as meeting tight deadlines, important social obligations or driving in heavy traffic, often bring about anxious feelings. Such mild anxiety may help make you alert and focused on facing threatening or challenging circumstances. On the other hand, anxiety disorders cause severe distress over a period of time and disrupt the lives of individuals suffering from them. The frequency and intensity of anxiety involved in these disorders is often debilitating. But fortunately, with proper and effective treatment, people suffering from anxiety disorders can lead normal lives.

Everyone feels anxious and under stress from time-to-time. Situations such as meeting tight deadlines, important social obligations or driving in heavy traffic, often bring about anxious feelings. Such mild anxiety may help make you alert and focused on facing threatening or challenging circumstances. On the other hand, anxiety disorders cause severe distress over a period of time and disrupt the lives of individuals suffering from them. The frequency and intensity of anxiety involved in these disorders is often debilitating. But fortunately, with proper and effective treatment, people suffering from anxiety disorders can lead normal lives. Bearden et al's review of what could be wrong with the brain reads like a neurologist's laundry list from hell: ventricular enlargements, cortical atrophy, cerebellar vermal atrophy, white matter hypertensities (especially in the frontal cortex and basal ganglia structures), greater left temporal lobe volume, increased amygdala volume, enlarged right hippocampal volume, hypoplasmia of the medial temporal lobe, and more. Then there's the matter of those chemical imbalances, such as glucose metabolism and phospholipid metabolism.

Bearden et al's review of what could be wrong with the brain reads like a neurologist's laundry list from hell: ventricular enlargements, cortical atrophy, cerebellar vermal atrophy, white matter hypertensities (especially in the frontal cortex and basal ganglia structures), greater left temporal lobe volume, increased amygdala volume, enlarged right hippocampal volume, hypoplasmia of the medial temporal lobe, and more. Then there's the matter of those chemical imbalances, such as glucose metabolism and phospholipid metabolism.