Describing Depression Among African-Amarican Women by Nikki Giovanni, Introspection

because she didn't know any better

she stayed alive

among the tired and lonely

not waiting always wanting

needing a good night's rest

Defining the Roots of Depression Among African-American Women

Clinical depression is often a vague disorder for African- American women. It may produce an abundance of "depressions" in the lives of the women who experience its ongoing, relentless symptoms. The old adage of "being sick and tired of being sick and tired" is quite relevant for these women, since they often suffer from persistent, untreated physical and emotional symptoms. If these women consult health professionals, they are frequently told that they are hypertensive, run down, or tense and nervous. They may be prescribed antihypertensives, vitamins, or mood elevating pills; or they may be informed to lose weight, learn to relax, get a change of scenery, or get more exercise. The root of their symptoms frequently is not explored; and these women continue to complain of being tired, weary, empty, lonely, sad. Other women friends and family members may say, "We all feel this way sometimes, it's just the way it is for us Black women."

I remember one of my clients, a woman who had been brought into the emergency mental health center because she had slashed her wrists while at work. During my assessment of her, she told me she felt like she was "dragging a weight around all the time." She said, "I've had all these tests done and they tell me physically everything is fine but I know it's not. Maybe I'm going crazy! Something is terribly wrong with me, but I don't have time for it. I've got a family who depends on me to be strong. I'm the one that everyone turns to." This woman, more conerned about her family than herself, said she "[felt] guilty spending so much time on [her]self." When I asked her if she had anyone she could talk to, she responded, "I don't want to bother my family and my closest friend is having her own problems right now." Her comments reflect and mirror the sentiments of other depressed African-American women I have seen in my practice: They're alive, but barely, and are continually tired, lonely, and wanting.

Statistics regarding depression in African-American women are either non-existent or uncertain. Part of this confusion is because past published clinical research on depression in African-American women has been scarce (Barbee, 1992; Carrington, 1980; McGrath et al., 1992; Oakley, 1986; Tomes et al., 1990). This scarcity is, in part, due to the fact that African-American women may not seek treatment for their depression, may be misdiagnosed, or may withdraw from treatment because their ethnic, cultural, and/or gender needs have not been met (Cannon, Higginbotham, Guy, 1989; Warren, 1994a). I also have found that African-American women may be reticent to participate in research studies because they are uncertain as to how research data will be disseminated or are afraid that data will be misinterpreted. In addition, there are few available culturally competent researchers who are knowledgeable regarding the phenomenon of depression in African-American women. Subsequently, African-American women may not be available to participate in depression research studies. Available published statistics concur with what I have seen in my practice: that African-American women report more depressive symptoms than African-American men or European-American women or men, and that these women have a depression rate twice that of European-American women (Brown, 1990; Kessler et al., 1994).

Statistics regarding depression in African-American women are either non-existent or uncertain. Part of this confusion is because past published clinical research on depression in African-American women has been scarce (Barbee, 1992; Carrington, 1980; McGrath et al., 1992; Oakley, 1986; Tomes et al., 1990). This scarcity is, in part, due to the fact that African-American women may not seek treatment for their depression, may be misdiagnosed, or may withdraw from treatment because their ethnic, cultural, and/or gender needs have not been met (Cannon, Higginbotham, Guy, 1989; Warren, 1994a). I also have found that African-American women may be reticent to participate in research studies because they are uncertain as to how research data will be disseminated or are afraid that data will be misinterpreted. In addition, there are few available culturally competent researchers who are knowledgeable regarding the phenomenon of depression in African-American women. Subsequently, African-American women may not be available to participate in depression research studies. Available published statistics concur with what I have seen in my practice: that African-American women report more depressive symptoms than African-American men or European-American women or men, and that these women have a depression rate twice that of European-American women (Brown, 1990; Kessler et al., 1994).

African-American women have a triple jeopardy status which places us at risk for developing depression (Boykin, 1985; Carrington, 1980; Taylor, 1992). We live in a majority-dominated society that frequently devalues our ethnicity, culture, and gender. In addition, we may find ourselves at the lower spectrum of the American political and economic continuum. Often we are involved in multiple roles as we attempt to survive economically and advance ourselves and our families through mainstream society. All of these factors intensify the amount of stress within our lives which can erode our self-esteem, social support systems, and health (Warren, 1994b).

Clinically, depression is described as a mood disorder with a collection of symptoms persisting over a two-week time. These symptoms must not be attributed to the direct physical effects of alcohol or drug abuse or other medication usage. However, clinical depression may occur in conjunction with these conditions as well as other emotional and physical disorders such as hormonal, blood pressure, kidney, or heart conditions (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994). To be diagnosed with clinical depression, an African-American woman must have either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure as well as four of the following symptoms:

- Depressed or irritable mood throughout the day (often everyday)

- Lack of pleasure in life activities

- Significant (more than 5%) weight loss or gain over a month

- Sleep disruptions (increased or decreased sleeping)

- Unusual, increased, agitated or decreased physical activity (generally everyday)

- Daily fatigue or lack of energy

- Daily feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- Inability to concentrate or make decisions

- Recurring thoughts of death or suicidal thoughts (APA, 1994).

The Meaning of Contextual Depression Theory

In the past, causal theories of depression have been used across all populations. These theories have utilized biological, psychosocial, and sociological weaknesses and changes to explain the occurrence and development of depression. However, I think that a contextual depression theory provides a more meaningful explanation for the occurrence of depression within African- American women. This contextual focus incorporates the neurochemical, genetic perspectives of biological theory; the impact of losses, stressors, and control/coping strategies of psychosocial theory; the conditioning patterns, social support systems, and social, political, and economic perspectives of sociological theory; and the ethnic and cultural influences which affect the physical and psychological development and health of African-American women (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Carrington, 1979, 1980; Cockerman, 1992; Collins, 1991; Coner-Edwards & Edwards, 1988; Freud, 1957; Klerman, 1989; Taylor, 1992; Warren, 1994b). Another important aspect of the contextual depression theory is that it incorporates an examination of the strengths of African- American women and the cultural competency of mental health professionals. Past depression theories traditionally have ignored these factors. Understanding these factors is important because depressed African-American women's assessment and treatment process is impacted not only by the women's attitudes but also by the attitudes of the health care professionals who provide services for them.

African-American women have strengths; we are survivors and innovators who historically have been involved in the development of family and group survival strategies (Giddings, 1992; Hooks, 1989). However, women may experience increased stress, guilt, and depressive symptoms when they have role conflicts between their family's survival and their own developmental needs (Carrington, 1980; Outlaw, 1993). It is this cumulative stress which takes a toll on the strengths of African-American women and can produce an erosion of emotional and physical health (Warren, 1994b).

Choosing a Treatment Path

Treatment strategies for depressed African-American women need to be based on contextual depression theory because it addresses women's total health status. African-American women's psychological and physiological health cannot be separated from their ethnic and cultural values. Mental health professionals, when culturally competent, acknowledge and understand African-American women's cultural strengths and values in order to successfully counsel them. Cultural competence involves a mental health professional's use of cultural awareness (sensitivity when interacting with other cultures), cultural knowledge (educational basis of other cultures' world views), cultural skill (the ability to conduct a cultural assessment), and cultural encounter (the ability to engage meaningfully in interactions with persons from different cultural arenas) (Campinha-Bacote, 1994; Capers, 1994).

Initially, I advise a woman to have a complete history and physical done to help determine the cause of her depression. I take a cultural assessment in conjunction with this history and physical. This assessment allows me to find out what is important for the woman in the areas of her ethnic, racial, and cultural background. I must complete this assessment before I can institute any interventions for the woman. Then I can spend time with her discussing her attitude toward her depression, what she thinks created her symptoms, and what the causes of depression are. This is important because depressed African-American women need to understand that depression is not a weakness, but an illness often resulting from a combination of causes. It is true that treating neurochemical imbalances or physical disorders may alleviate the depression; however, surgeries or certain heart, hormonal, blood pressure, or kidney medications actually may induce one. Consequently, it is important to provide a woman with information regarding this possibility and perhaps to alter or change any medications that she is taking.

I also like to screen women for their level of depression using either the Beck Depression Inventory or the Zung Self- Rating Scale. Both of these instruments are quick and easy to complete and have excellent reliability and validity. Antidepressants may provide relief for women by restoring neurochemical balances. However, African-American women may be more sensitive to certain antidepressants and may require smaller dosages than traditional treatment advises (McGrath et al., 1992). I like to provide women with information on the different types of antidepressant medications and their effects and to monitor their progress on medication(s). Women also should be given information regarding the symptoms of depression so they may recognize changes within their current condition and any future recurrence of depressive symptoms. Information regarding light, nutrition, exercise, and electroshock therapies may be included. An excellent booklet that I use, which is available for free through local mental health centers or agencies, is Depression Is a Treatable Illness: A Patient's Guide, Publication #AHCPR 93- 0553 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1993).

I also advise that women participate in some form of individual or group therapeutic discussion sessions with either myself or another trained therapist. These sessions can help them to understand their depression and their treatment choices, enhance their self-esteem, and develop alternative strategies in order to handle their stress and conflicting roles appropriately. I advise these women to learn relaxation techniques and develop alternative coping and crisis management strategies. Group sessions may be more supportive for some women and may facilitate the development of a wider selection of lifestyle choices and changes. Self-help groups, such as the National Black Women's Health Project, also may provide social support for depressed African-American women as well as enhance the work women accomplish with their therapeutic sessions. Finally, women need to monitor their ongoing emotional and physical health as they progress through life and "rise," as Maya Angelou writes, "into a day break that's wondrously clear . . . bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave" (1994, p. 164).

Barbara Jones Warren, R.N., M.S., Ph.D., is a psychiatric mental health nurse consultant. Formerly an American Nurses Foundation Ethnic/Racial Minority Fellow, she has joined the faculty of The Ohio State University.

References for article:

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49-74. American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder-IV [DSM-IV]. (4th ed.) Washington, DC: Author. Angelou, M. (1994). And still I rise. In M. Angelou (Ed.), The complete collected poems of Maya Angelou (pp. 163-164). New York: Random House. Barbee, E. L. (1992). African-American women and depression: A review and critique of the literature. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 6(5), 257-265. Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. E., and Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford. Brown, D. R. (1990). Depression among Blacks: An epidemiological perspective. In D. S. Ruiz and J. P. Comer (Eds.), Handbook of mental health and mental disorder among Black Americans (pp. 71-93). New York: Greenwood Press. Campinha-Bacote, J. (1994). Cultural competence in psychiatric mental health nursing: A conceptual model. Nursing Clinics of North America, 29(1), 1-8. Cannon, L. W., Higgenbotham, E., & Guy, R. F. (1989). Depression among women: Exploring the effects of race, class, and gender. Memphis, TN: Center for Research on Women, Memphis State University. Capers, C. F. (1994). Mental health issues and African-Americans. Nursing Clinics of North America, 29(1), 57-64. Carrington, C. H. (1979). A comparison of cognitive and analytically oriented brief treatment approaches to depression in Black women. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, Baltimore. Carrington, C. H. (1980). Depression in Black women: A theoretical perspective. In L. Rodgers-Rose (Ed.), The Black woman (pp. 265-271). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Cockerman, W. C. (1992). Sociology of mental disorder. (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Collins, P. H. (1991). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. Coner-Edwards, A. F., & Edwards, H. E. (1988). The Black middle class: Definition and demographics. In A.F. Coner-Edwards & J. Spurlock (Eds.), Black families in crisis: The middle class (pp. 1-13). New York: Brunner Mazel. Freud, S. (1957). Mourning and melancholia. (Standard ed., vol. 14). London: Hogarth Press. Giddings, P. (1992). The last taboo. In T. Morrison (Ed.), Race-ing justice, en-gendering power (pp. 441-465). New York: Pantheon Books. Giovanni, N. (1980). Poems by Nikki Giovanni: Cotton candy on a rainy day. New York: Morrow. Hooks, B. (1989). Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking black. Boston, MA: South End Press. Kessler, R. C., McGongle, K. A., Zhao, S., Nelson, C. B., Hughes, H., Eshelman, S., Wittchen, H., & Kendler, K. S. (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the U.S. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8-19. Klerman, G. L. (1989). The interperson model. In J. J. Mann (Ed.), Models of depressive disorders (pp. 45-77). New York: Plenum. McGrath, E., Keita, G. P., Strickland, B. R., & Russo, N. F. (1992). Women and depression: Risk factors and treatment issues. (3rd printing). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Oakley, L. D. (1986). Marital status, gender role attitude, and women's report of depression. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association, 1(1), 41-51. Outlaw, F. H. (1993). Stress and coping: The influence of racism on the cognitive appraisal processing of African Americans. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 14, 399-409. Taylor, S. E. (1992). The mental health status of Black Americans: An overview. In R. L. Braithwate & S. E. Taylor (Eds.), Health issues in the Black community (pp. 20-34). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Tomes, E. K., Brown, A., Semenya, K., & Simpson, J. (1990). Depression in Black women of low socioeconomic status: Psychological factors and nursing diagnosis. The Journal of The National Black Nurses Association, 4(2), 37-46. Warren, B. J. (1994a). Depression in African-American women. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 32(3), 29-33. Warren, B. J. (1994b). The experience of depression for African-American women. In B. J. McElmurry & R. S. Parker (Eds.), Second annual review of women's health. New York:National League for Nursing Press. Woods, N. F., Lentz, M., Mitchell, E., & Oakley, L. D. (1994). Depressed mood and self-esteem in young Asian, Black, and White women in America. Health Care for Women International, 15, 243-262.

next: A Hidden Disease: In Older Blacks, Depression Often Goes Untreated

~ depression library articles

~ all articles on depression

Statistics regarding depression in African-American women are either non-existent or uncertain. Part of this confusion is because past published clinical research on depression in African-American women has been scarce (Barbee, 1992; Carrington, 1980; McGrath et al., 1992; Oakley, 1986; Tomes et al., 1990). This scarcity is, in part, due to the fact that African-American women may not seek treatment for their depression, may be misdiagnosed, or may withdraw from treatment because their ethnic, cultural, and/or gender needs have not been met (Cannon, Higginbotham, Guy, 1989; Warren, 1994a). I also have found that African-American women may be reticent to participate in research studies because they are uncertain as to how research data will be disseminated or are afraid that data will be misinterpreted. In addition, there are few available culturally competent researchers who are knowledgeable regarding the phenomenon of depression in African-American women. Subsequently, African-American women may not be available to participate in depression research studies. Available published statistics concur with what I have seen in my practice: that African-American women report more depressive symptoms than African-American men or European-American women or men, and that these women have a depression rate twice that of European-American women (Brown, 1990; Kessler et al., 1994).

Statistics regarding depression in African-American women are either non-existent or uncertain. Part of this confusion is because past published clinical research on depression in African-American women has been scarce (Barbee, 1992; Carrington, 1980; McGrath et al., 1992; Oakley, 1986; Tomes et al., 1990). This scarcity is, in part, due to the fact that African-American women may not seek treatment for their depression, may be misdiagnosed, or may withdraw from treatment because their ethnic, cultural, and/or gender needs have not been met (Cannon, Higginbotham, Guy, 1989; Warren, 1994a). I also have found that African-American women may be reticent to participate in research studies because they are uncertain as to how research data will be disseminated or are afraid that data will be misinterpreted. In addition, there are few available culturally competent researchers who are knowledgeable regarding the phenomenon of depression in African-American women. Subsequently, African-American women may not be available to participate in depression research studies. Available published statistics concur with what I have seen in my practice: that African-American women report more depressive symptoms than African-American men or European-American women or men, and that these women have a depression rate twice that of European-American women (Brown, 1990; Kessler et al., 1994). The bipolar (also called the manic-depressive) illness, caused by as yet unknown imbalances of neurotransmitters in the brain, is know to wreak havoc with countless lives in this country and all over the world. My interest in the illness stems from the fact that my father (now deceased) had it (the illness first manifested itself when I was around fourteen or fifteen). Needless to say, it placed significant emotional burden on me and my family. In retrospect however, I realize that a lot of the pain and suffering (for us anyway) was due simply to misinformation and/or lack of information about the illness. Although things are improving, especially in the U.S. and in the western hemisphere at least, I feel that the bipolar illness (unfortunately) still remains taboo and a cause of much unnecessary suffering for the patient and for the family/caregivers involved. This website is my minuscule effort to correct this situation.

The bipolar (also called the manic-depressive) illness, caused by as yet unknown imbalances of neurotransmitters in the brain, is know to wreak havoc with countless lives in this country and all over the world. My interest in the illness stems from the fact that my father (now deceased) had it (the illness first manifested itself when I was around fourteen or fifteen). Needless to say, it placed significant emotional burden on me and my family. In retrospect however, I realize that a lot of the pain and suffering (for us anyway) was due simply to misinformation and/or lack of information about the illness. Although things are improving, especially in the U.S. and in the western hemisphere at least, I feel that the bipolar illness (unfortunately) still remains taboo and a cause of much unnecessary suffering for the patient and for the family/caregivers involved. This website is my minuscule effort to correct this situation. Although depression is a common and troubling problem among the elderly, a July 2000 study suggests that its symptoms are being overlooked in many older black people. Elderly white people, the study found, are more than three times as likely to be prescribed anti-depressant drugs as elderly blacks.

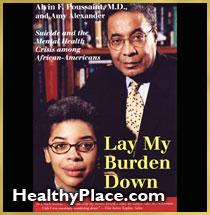

Although depression is a common and troubling problem among the elderly, a July 2000 study suggests that its symptoms are being overlooked in many older black people. Elderly white people, the study found, are more than three times as likely to be prescribed anti-depressant drugs as elderly blacks. "He was just very wonderful," recalls Amy Alexander, author of

"He was just very wonderful," recalls Amy Alexander, author of  At her cousin's wedding, Melissa, 14, looked around at the female guests and imagined what the kids at school would say: What a bunch of porkers. "Right there," says Melissa, who was teased for being slightly overweight in junior high school, "I decided I was going to be different."

At her cousin's wedding, Melissa, 14, looked around at the female guests and imagined what the kids at school would say: What a bunch of porkers. "Right there," says Melissa, who was teased for being slightly overweight in junior high school, "I decided I was going to be different." Teenage girls usually don't shoot up six inches over a summer the way boys often do, but they still need nearly as much food to fuel their growing bodies. And they need the right mix of calories, notes Tuttle. In general, girls aged 11 to 18 need 2,200 calories a day--more if they're physically active. Of that, 40 to 50 percent should come from carbohydrates, 20 to 30 percent from protein and no more than 30 percent from the good fats found in olive oil, avocados and nuts. "Teenage girls should also get plenty of calcium, iron, zinc and vitamins D and [B.sub.12]," says Tuttle. Here's what the National Academy of Sciences recommends your daughter take in every day:

Teenage girls usually don't shoot up six inches over a summer the way boys often do, but they still need nearly as much food to fuel their growing bodies. And they need the right mix of calories, notes Tuttle. In general, girls aged 11 to 18 need 2,200 calories a day--more if they're physically active. Of that, 40 to 50 percent should come from carbohydrates, 20 to 30 percent from protein and no more than 30 percent from the good fats found in olive oil, avocados and nuts. "Teenage girls should also get plenty of calcium, iron, zinc and vitamins D and [B.sub.12]," says Tuttle. Here's what the National Academy of Sciences recommends your daughter take in every day: We all know the benefits of exercise, and it seems that everywhere we turn, we hear that we should exercise more. The right kind of exercise does many great things for your body and soul: It can strengthen your heart and muscles, lower your body fat, and reduce your risk of many diseases.

We all know the benefits of exercise, and it seems that everywhere we turn, we hear that we should exercise more. The right kind of exercise does many great things for your body and soul: It can strengthen your heart and muscles, lower your body fat, and reduce your risk of many diseases. If you have been thinking about suicide, get help right away, rather than simply hoping your mood might improve. When a person has been feeling down for so long, it's hard for him to understand that suicide isn't the answer - it's a permanent solution to a temporary problem. Talk to anyone you know as soon as you can - a friend, a coach, a relative, a school counselor, a religious leader, a teacher, or any trusted adult. Call your local emergency number or check in the front pages of your phone book for the number of a local suicide crisis line. These toll-free lines are staffed 24 hours a day, 7 days a week by trained professionals who can help you without ever knowing your name or seeing your face. All calls are confidential - nothing is written down and no one you know will ever find out that you've called. There is also a National Suicide Helpline - 1-800-SUICIDE.

If you have been thinking about suicide, get help right away, rather than simply hoping your mood might improve. When a person has been feeling down for so long, it's hard for him to understand that suicide isn't the answer - it's a permanent solution to a temporary problem. Talk to anyone you know as soon as you can - a friend, a coach, a relative, a school counselor, a religious leader, a teacher, or any trusted adult. Call your local emergency number or check in the front pages of your phone book for the number of a local suicide crisis line. These toll-free lines are staffed 24 hours a day, 7 days a week by trained professionals who can help you without ever knowing your name or seeing your face. All calls are confidential - nothing is written down and no one you know will ever find out that you've called. There is also a National Suicide Helpline - 1-800-SUICIDE.