Provigil: Treatment for Wakefulness (Full Prescribing Information)

Brand Name: Provigil

Generic Name: Modafinil

Contents:

Description

Pharmacology

Clinical Trails

Indications and Usage

Contraindications

Warnings

Precautions

Adverse Reactions

Drug Abuse and Dependence

Overdosage

Dosage and Administration

How Supplied

Provigil (modafinil) patient information sheet (in plain English)

Description

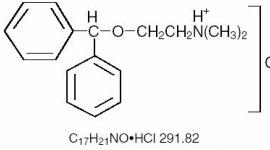

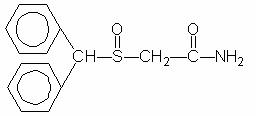

Provigil (modafinil) is a wakefulness-promoting agent for oral administration. Modafinil is a racemic compound. The chemical name for modafinil is 2-[(diphenylmethyl)sulfinyl]acetamide. The molecular formula is C15H15NO2S and the molecular weight is 273.35.

The chemical structure is:

Modafinil is a white to off-white, crystalline powder that is practically insoluble in water and cyclohexane. It is sparingly to slightly soluble in methanol and acetone. Provigil tablets contain 100 mg or 200 mg of modafinil and the following inactive ingredients: lactose, microcrystalline cellulose, pregelatinized starch, croscarmellose sodium, povidone, and magnesium stearate.

Clinical Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action and Pharmacology

The precise mechanism(s) through which modafinil promotes wakefulness is unknown. Modafinil has wake-promoting actions similar to sympathomimetic agents like amphetamine and methylphenidate, although the pharmacologic profile is not identical to that of sympathomimetic amines.

Modafinil has weak to negligible interactions with receptors for norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, GABA, adenosine, histamine-3, melatonin, and benzodiazepines. Modafinil also does not inhibit the activities of MAO-B or phosphodiesterases II-V.

Modafinil-induced wakefulness can be attenuated by the α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist prazosin; however, modafinil is inactive in other in vitro assay systems known to be responsive to α-adrenergic agonists, such as the rat vas deferens preparation.

Modafinil is not a direct- or indirect-acting dopamine receptor agonist. However, in vitro, modafinil binds to the dopamine transporter and inhibits dopamine reuptake. This activity has been associated in vivo with increased extracellular dopamine levels in some brain regions of animals. In genetically engineered mice lacking the dopamine transporter (DAT), modafinil lacked wake-promoting activity, suggesting that this activity was DAT-dependent. However, the wake-promoting effects of modafinil, unlike those of amphetamine, were not antagonized by the dopamine receptor antagonist haloperidol in rats. In addition, alpha-methyl-p-tyrosine, a dopamine synthesis inhibitor, blocks the action of amphetamine, but does not block locomotor activity induced by modafinil.

In the cat, equal wakefulness-promoting doses of methylphenidate and amphetamine increased neuronal activation throughout the brain. Modafinil at an equivalent wakefulness-promoting dose selectively and prominently increased neuronal activation in more discrete regions of the brain. The relationship of this finding in cats to the effects of modafinil in humans is unknown.

In addition to its wake-promoting effects and ability to increase locomotor activity in animals, modafinil produces psychoactive and euphoric effects, alterations in mood, perception, thinking, and feelings typical of other CNS stimulants in humans. Modafinil has reinforcing properties, as evidenced by its self-administration in monkeys previously trained to self-administer cocaine. Modafinil was also partially discriminated as stimulant-like.

The optical enantiomers of modafinil have similar pharmacological actions in animals. Two major metabolites of modafinil, modafinil acid and modafinil sulfone, do not appear to contribute to the CNS-activating properties of modafinil.

Pharmacokinetics

Modafinil is a racemic compound, whose enantiomers have different pharmacokinetics (e.g., the half-life of the l-isomer is approximately three times that of the d-isomer in adult humans). The enantiomers do not interconvert. At steady state, total exposure to the l-isomer is approximately three times that for the d-isomer. The trough concentration (Cminss) of circulating modafinil after once daily dosing consists of 90% of the l-isomer and 10% of the d-isomer. The effective elimination half-life of modafinil after multiple doses is about 15 hours. The enantiomers of modafinil exhibit linear kinetics upon multiple dosing of 200-600 mg/day once daily in healthy volunteers. Apparent steady states of total modafinil and l-(-)-modafinil are reached after 2-4 days of dosing.

Absorption

Absorption of Provigil tablets is rapid, with peak plasma concentrations occurring at 2-4 hours. The bioavailability of Provigil tablets is approximately equal to that of an aqueous suspension. The absolute oral bioavailability was not determined due to the aqueous insolubility (<1 mg/mL) of modafinil, which precluded intravenous administration. Food has no effect on overall Provigil bioavailability; however, its absorption (tmax) may be delayed by approximately one hour if taken with food.

Distribution

Modafinil is well distributed in body tissue with an apparent volume of distribution (~0.9 L/kg) larger than the volume of total body water (0.6 L/kg). In human plasma, in vitro, modafinil is moderately bound to plasma protein (~60%, mainly to albumin). At serum concentrations obtained at steady state after doses of 200 mg/day, modafinil exhibits no displacement of protein binding of warfarin, diazepam or propranolol. Even at much larger concentrations (1000 µM; > 25 times the Cmax of 40 µM at steady state at 400 mg/day), modafinil has no effect on warfarin binding. Modafinil acid at concentrations >500 µM decreases the extent of warfarin binding, but these concentrations are >35 times those achieved therapeutically.

Metabolism and Elimination

The major route of elimination is metabolism (~90%), primarily by the liver, with subsequent renal elimination of the metabolites. Urine alkalinization has no effect on the elimination of modafinil.

Metabolism occurs through hydrolytic deamidation, S-oxidation, aromatic ring hydroxylation, and glucuronide conjugation. Less than 10% of an administered dose is excreted as the parent compound. In a clinical study using radiolabeled modafinil, a total of 81% of the administered radioactivity was recovered in 11 days post-dose, predominantly in the urine (80% vs. 1.0% in the feces). The largest fraction of the drug in urine was modafinil acid, but at least six other metabolites were present in lower concentrations. Only two metabolites reach appreciable concentrations in plasma, i.e., modafinil acid and modafinil sulfone. In preclinical models, modafinil acid, modafinil sulfone, 2-[(diphenylmethyl)sulfonyl]acetic acid and 4-hydroxy modafinil, were inactive or did not appear to mediate the arousal effects of modafinil.

In adults, decreases in trough levels of modafinil have sometimes been observed after multiple weeks of dosing, suggesting auto-induction, but the magnitude of the decreases and the inconsistency of their occurrence suggest that their clinical significance is minimal. Significant accumulation of modafinil sulfone has been observed after multiple doses due to its long elimination half-life of 40 hours. Induction of metabolizing enzymes, most importantly cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 3A4, has also been observed in vitro after incubation of primary cultures of human hepatocytes with modafinil and in vivo after extended administration of modafinil at 400 mg/day. (For further discussion of the effects of modafinil on CYP enzyme activities, see PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions.)

Drug-Drug Interactions:

Based on in vitro data, modafinil is metabolized partially by the 3A isoform subfamily of hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP3A4). In addition, modafinil has the potential to inhibit CYP2C19, suppress CYP2C9, and induce CYP3A4, CYP2B6, and CYP1A2. Because modafinil and modafinil sulfone are reversible inhibitors of the drug-metabolizing enzyme CYP2C19, co-administration of modafinil with drugs such as diazepam, phenytoin and propranolol, which are largely eliminated via that pathway, may increase the circulating levels of those compounds. In addition, in individuals deficient in the enzyme CYP2D6 (i.e., 7-10% of the Caucasian population; similar or lower in other populations), the levels of CYP2D6 substrates such as tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which have ancillary routes of elimination through CYP2C19, may be increased by co-administration of modafinil. Dose adjustments may be necessary for patients being treated with these and similar medications (See PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions). An in vitro study demonstrated that armodafinil (one of the enantiomers of modafinil) is a substrate of P-glycoprotein.

Coadministration of modafinil with other CNS active drugs such as methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine did not significantly alter the pharmacokinetics of either drug.

Chronic administration of modafinil 400 mg was found to decrease the systemic exposure to two CYP3A4 substrates, ethinyl estradiol and triazolam, after oral administration suggesting that CYP3A4 had been induced. Chronic administration of modafinil can increase the elimination of substrates of CYP3A4. Dose adjustments may be necessary for patients being treated with these and similar medications (See PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions).

An apparent concentration-related suppression of CYP2C9 activity was observed in human hepatocytes after exposure to modafinil in vitro suggesting that there is a potential for a metabolic interaction between modafinil and the substrates of this enzyme (e.g., S-warfarin, phenytoin). However, in an interaction study in healthy volunteers, chronic modafinil treatment did not show a significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of warfarin when compared to placebo. (See PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions,Other Drugs, Warfarin).

Special Populations

Gender Effect:

The pharmacokinetics of modafinil are not affected by gender.

Age Effect:

A slight decrease (~20%) in the oral clearance (CL/F) of modafinil was observed in a single dose study at 200 mg in 12 subjects with a mean age of 63 years (range 53 - 72 years), but the change was considered not likely to be clinically significant. In a multiple dose study (300 mg/day) in 12 patients with a mean age of 82 years (range 67 - 87 years), the mean levels of modafinil in plasma were approximately two times those historically obtained in matched younger subjects. Due to potential effects from the multiple concomitant medications with which most of the patients were being treated, the apparent difference in modafinil pharmacokinetics may not be attributable solely to the effects of aging. However, the results suggest that the clearance of modafinil may be reduced in the elderly (See Dosage and Administration).

Race Effect:

The influence of race on the pharmacokinetics of modafinil has not been studied.

Renal Impairment:

In a single dose 200 mg modafinil study, severe chronic renal failure (creatinine clearance ≤ 20 mL/min) did not significantly influence the pharmacokinetics of modafinil, but exposure to modafinil acid (an inactive metabolite) was increased 9-fold (See PRECAUTIONS).

Hepatic Impairment:

Pharmacokinetics and metabolism were examined in patients with cirrhosis of the liver (6 males and 3 females). Three patients had stage B or B+ cirrhosis (per the Child criteria) and 6 patients had stage C or C+ cirrhosis. Clinically 8 of 9 patients were icteric and all had ascites. In these patients, the oral clearance of modafinil was decreased by about 60% and the steady state concentration was doubled compared to normal patients. The dose of Provigil should be reduced in patients with severe hepatic impairment (See PRECAUTIONS and Dosage and Administration).

Clinical Trails

The effectiveness of Provigil in reducing excessive sleepiness has been established in the following sleep disorders: narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS), and shift work sleep disorder (SWSD).

Narcolepsy

The effectiveness of Provigil in reducing the excessive sleepiness (ES) associated with narcolepsy was established in two US 9-week, multicenter, placebo-controlled, two-dose (200 mg per day and 400 mg per day) parallel-group, double-blind studies of outpatients who met the ICD-9 and American Sleep Disorders Association criteria for narcolepsy (which are also consistent with the American Psychiatric Association DSM-IV criteria). These criteria include either 1) recurrent daytime naps or lapses into sleep that occur almost daily for at least three months, plus sudden bilateral loss of postural muscle tone in association with intense emotion (cataplexy) or 2) a complaint of excessive sleepiness or sudden muscle weakness with associated features: sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations, automatic behaviors, disrupted major sleep episode; and polysomnography demonstrating one of the following: sleep latency less than 10 minutes or rapid eye movement (REM) sleep latency less than 20 minutes. In addition, for entry into these studies, all patients were required to have objectively documented excessive daytime sleepiness, a Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) with two or more sleep onset REM periods, and the absence of any other clinically significant active medical or psychiatric disorder. The MSLT, an objective daytime polysomnographic assessment of the patient's ability to fall asleep in an unstimulating environment, measures latency (in minutes) to sleep onset averaged over 4 test sessions at 2-hour intervals following nocturnal polysomnography. For each test session, the subject was told to lie quietly and attempt to sleep. Each test session was terminated after 20 minutes if no sleep occurred or 15 minutes after sleep onset.

In both studies, the primary measures of effectiveness were 1) sleep latency, as assessed by the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT) and 2) the change in the patient's overall disease status, as measured by the Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI-C). For a successful trial, both measures had to show significant improvement.

The MWT measures latency (in minutes) to sleep onset averaged over 4 test sessions at 2 hour intervals following nocturnal polysomnography. For each test session, the subject was asked to attempt to remain awake without using extraordinary measures. Each test session was terminated after 20 minutes if no sleep occurred or 10 minutes after sleep onset. The CGI-C is a 7-point scale, centered at No Change, and ranging from Very Much Worse to Very Much Improved. Patients were rated by evaluators who had no access to any data about the patients other than a measure of their baseline severity. Evaluators were not given any specific guidance about the criteria they were to apply when rating patients.

Other assessments of effect included the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS; a series of questions designed to assess the degree of sleepiness in everyday situations) the Steer Clear Performance Test (SCPT; a computer-based evaluation of a patient's ability to avoid hitting obstacles in a simulated driving situation), standard nocturnal polysomnography, and patient's daily sleep log. Patients were also assessed with the Quality of Life in Narcolepsy (QOLIN) scale, which contains the validated SF-36 health questionnaire.

Both studies demonstrated improvement in objective and subjective measures of excessive daytime sleepiness for both the 200 mg and 400 mg doses compared to placebo. Patients treated with either dose of Provigil showed a statistically significantly enhanced ability to remain awake on the MWT (all p values <0.001) at weeks 3, 6, 9, and final visit compared to placebo and a statistically significantly greater global improvement, as rated on the CGI-C scale (all p values <0.05).

The average sleep latencies (in minutes) on the MWT at baseline for the 2 controlled trials are shown in Table 1 below, along with the average change from baseline on the MWT at final visit.

The percentages of patients who showed any degree of improvement on the CGI-C in the two clinical trials are shown in Table 2 below.

Similar statistically significant treatment-related improvements were seen on other measures of impairment in narcolepsy, including a patient assessed level of daytime sleepiness on the ESS (p<0.001 for each dose in comparison to placebo).

Nighttime sleep measured with polysomnography was not affected by the use of Provigil.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea/Hypopnea Syndrome (OSAHS)

The effectiveness of Provigil in reducing the excessive sleepiness associated with OSAHS was established in two clinical trials. In both studies, patients were enrolled who met the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) criteria for OSAHS (which are also consistent with the American Psychiatric Association DSM-IV criteria). These criteria include either, 1) excessive sleepiness or insomnia, plus frequent episodes of impaired breathing during sleep, and associated features such as loud snoring, morning headaches and dry mouth upon awakening; or 2) excessive sleepiness or insomnia and polysomnography demonstrating one of the following: more than five obstructive apneas, each greater than 10 seconds in duration, per hour of sleep and one or more of the following: frequent arousals from sleep associated with the apneas, bradytachycardia, and arterial oxygen desaturation in association with the apneas. In addition, for entry into these studies, all patients were required to have excessive sleepiness as demonstrated by a score ≥10 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, despite treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Evidence that CPAP was effective in reducing episodes of apnea/hypopnea was required along with documentation of CPAP use.

In the first study, a 12-week multicenter placebo-controlled trial, a total of 327 patients were randomized to receive Provigil 200 mg/day, Provigil 400 mg/day, or matching placebo. The majority of patients (80%) were fully compliant with CPAP, defined as CPAP use > 4 hours/night on > 70% nights. The remainder were partially CPAP compliant, defined as CPAP use 30% nights. CPAP use continued throughout the study. The primary measures of effectiveness were 1) sleep latency, as assessed by the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT) and 2) the change in the patient's overall disease status, as measured by the Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI-C) at week 12 or the final visit. (See Clinical Trails, Narcolepsy section above for a description of these tests.)

Patients treated with Provigil showed a statistically significant improvement in the ability to remain awake compared to placebo-treated patients as measured by the MWT (p<0.001) at endpoint [Table 1]. Provigil-treated patients also showed a statistically significant improvement in clinical condition as rated by the CGI-C scale (p<0.001) [Table 2]. The two doses of Provigil performed similarly.

In the second study, a 4-week multicenter placebo-controlled trial, 157 patients were randomized to either Provigil 400 mg/day or placebo. Documentation of regular CPAP use (at least 4 hours/night on 70% of nights) was required for all patients. The primary outcome measure was the change from baseline on the ESS at week 4 or final visit. The baseline ESS scores for the Provigil and placebo groups were 14.2 and 14.4, respectively. At week 4, the ESS was reduced by 4.6 in the Provigil group and by 2.0 in the placebo group, a difference that was statistically significant (p<0.0001).

Nighttime sleep measured with polysomnography was not affected by the use of Provigil.

Shift Work Sleep Disorder (SWSD)

The effectiveness of Provigil for the excessive sleepiness associated with SWSD was demonstrated in a 12-week placebo-controlled clinical trial. A total of 209 patients with chronic SWSD were randomized to receive Provigil 200 mg/day or placebo. All patients met the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-10) criteria for chronic SWSD (which are consistent with the American Psychiatric Association DSM-IV criteria for Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder: Shift Work Type). These criteria include 1) either: a) a primary complaint of excessive sleepiness or insomnia which is temporally associated with a work period (usually night work) that occurs during the habitual sleep phase, or b) polysomnography and the MSLT demonstrate loss of a normal sleep-wake pattern (i.e., disturbed chronobiological rhythmicity); and 2) no other medical or mental disorder accounts for the symptoms, and 3) the symptoms do not meet criteria for any other sleep disorder producing insomnia or excessive sleepiness (e.g., time zone change [jet lag] syndrome).

It should be noted that not all patients with a complaint of sleepiness who are also engaged in shift work meet the criteria for the diagnosis of SWSD. In the clinical trial, only patients who were symptomatic for at least 3 months were enrolled.

Enrolled patients were also required to work a minimum of 5 night shifts per month, have excessive sleepiness at the time of their night shifts (MSLT score < 6 minutes), and have daytime insomnia documented by a daytime polysomnogram (PSG).

The primary measures of effectiveness were 1) sleep latency, as assessed by the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) performed during a simulated night shift at week 12 or the final visit and 2) the change in the patient's overall disease status, as measured by the Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI-C) at week 12 or the final visit. Patients treated with Provigil showed a statistically significant prolongation in the time to sleep onset compared to placebo-treated patients, as measured by the nighttime MSLT [Table 1] (p<0.05). Improvement on the CGI-C was also observed to be statistically significant (p<0.001). (See Clinical Trails, Narcolepsy section above for a description of these tests.)

Daytime sleep measured with polysomnography was not affected by the use of Provigil.

HTML clipboard

| Disorder | Measure | Provigil 200 mg* |

Provigil 400 mg* |

Placebo | |||

| *Significantly different than placebo for all trials (p<0.01 for all trials but SWSD, which was p<0.05) | |||||||

| Baseline | Change from Baseline |

Baseline | Change from Baseline |

Baseline | Change from Baseline |

||

| Narcolepsy I | MWT | 5.8 | 2.3 | 6.6 | 2.3 | 5.8 | -0.7 |

| Narcolepsy II | MWT | 6.1 | 2.2 | 5.9 | 2.0 | 6.0 | -0.7 |

| OSAHS | MWT | 13.1 | 1.6 | 13.6 | 1.5 | 13.8 | -1.1 |

| SWSD | MSLT | 2.1 | 1.7 | - | - | 2.0 | 0.3 |

| Disorder | Provigil 200 mg* |

Provigil 400 mg* |

Placebo |

| *Significantly different than placebo for all trials (p<0.01) | |||

| Narcolepsy I | 64% | 72% | 37% |

| Narcolepsy II | 58% | 60% | 38% |

| OSAHS | 61% | 68% | 37% |

| SWSD | 74% | - | 36% |

Indications and Usage

Provigil is indicated to improve wakefulness in adult patients with excessive sleepiness associated with narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome, and shift work sleep disorder.

In OSAHS, Provigil is indicated as an adjunct to standard treatment(s) for the underlying obstruction. If continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the treatment of choice for a patient, a maximal effort to treat with CPAP for an adequate period of time should be made prior to initiating Provigil. If Provigil is used adjunctively with CPAP, the encouragement of and periodic assessment of CPAP compliance is necessary.

In all cases, careful attention to the diagnosis and treatment of the underlying sleep disorder(s) is of utmost importance. Prescribers should be aware that some patients may have more than one sleep disorder contributing to their excessive sleepiness.

The effectiveness of modafinil in long-term use (greater than 9 weeks in Narcolepsy clinical trials and 12 weeks in OSAHS and SWSD clinical trials) has not been systematically evaluated in placebo-controlled trials. The physician who elects to prescribe Provigil for an extended time in patients with Narcolepsy, OSAHS, or SWSD should periodically reevaluate long-term usefulness for the individual patient.

Contraindications

Provigil is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to modafinil, armodafinil or its inactive ingredients.

Warnings

Serious Rash, including Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

Serious rash requiring hospitalization and discontinuation of treatment has been reported in adults and children in association with the use of modafinil.

Modafinil is not approved for use in pediatric patients for any indication.

In clinical trials of modafinil, the incidence of rash resulting in discontinuation was approximately 0.8% (13 per 1,585) in pediatric patients (age <17 years); these rashes included 1 case of possible Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and 1 case of apparent multi-organ hypersensitivity reaction. Several of the cases were associated with fever and other abnormalities (e.g., vomiting, leukopenia). The median time to rash that resulted in discontinuation was 13 days. No such cases were observed among 380 pediatric patients who received placebo. No serious skin rashes have been reported in adult clinical trials (0 per 4,264) of modafinil.

Rare cases of serious or life-threatening rash, including SJS, Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), and Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) have been reported in adults and children in worldwide post-marketing experience. The reporting rate of TEN and SJS associated with modafinil use, which is generally accepted to be an underestimate due to underreporting, exceeds the background incidence rate. Estimates of the background incidence rate for these serious skin reactions in the general population range between 1 to 2 cases per million-person years.

There are no factors that are known to predict the risk of occurrence or the severity of rash associated with modafinil. Nearly all cases of serious rash associated with modafinil occurred within 1 to 5 weeks after treatment initiation. However, isolated cases have been reported after prolonged treatment (e.g., 3 months). Accordingly, duration of therapy cannot be relied upon as a means to predict the potential risk heralded by the first appearance of a rash.

Although benign rashes also occur with modafinil, it is not possible to reliably predict which rashes will prove to be serious. Accordingly, modafinil should ordinarily be discontinued at the first sign of rash, unless the rash is clearly not drug-related. Discontinuation of treatment may not prevent a rash from becoming life-threatening or permanently disabling or disfiguring.

Angioedema and Anaphylactoid Reactions

One serious case of angioedema and one case of hypersensitivity (with rash, dysphagia, and bronchospasm), were observed among 1,595 patients treated with armodafinil, the R enantiomer of modafinil (which is the racemic mixture). No such cases were observed in modafinil clinical trials. However, angioedema has been reported in postmarketing experience with modafinil. Patients should be advised to discontinue therapy and immediately report to their physician any signs or symptoms suggesting angioedema or anaphylaxis (e.g., swelling of face, eyes, lips, tongue or larynx; difficulty in swallowing or breathing; hoarseness).

Multi-organ Hypersensitivity Reactions

Multi-organ hypersensitivity reactions, including at least one fatality in postmarketing experience, have occurred in close temporal association (median time to detection 13 days: range 4-33) to the initiation of modafinil.

Although there have been a limited number of reports, multi-organ hypersensitivity reactions may result in hospitalization or be life-threatening. There are no factors that are known to predict the risk of occurrence or the severity of multi-organ hypersensitivity reactions associated with modafinil. Signs and symptoms of this disorder were diverse; however, patients typically, although not exclusively, presented with fever and rash associated with other organ system involvement. Other associated manifestations included myocarditis, hepatitis, liver function test abnormalities, hematological abnormalities (e.g., eosinophilia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), pruritus, and asthenia. Because multi-organ hypersensitivity is variable in its expression, other organ system symptoms and signs, not noted here, may occur.

If a multi-organ hypersensitivity reaction is suspected, Provigil should be discontinued. Although there are no case reports to indicate cross-sensitivity with other drugs that produce this syndrome, the experience with drugs associated with multi-organ hypersensitivity would indicate this to be a possibility.

Persistent Sleepiness

Patients with abnormal levels of sleepiness who take Provigil should be advised that their level of wakefulness may not return to normal. Patients with excessive sleepiness, including those taking Provigil, should be frequently reassessed for their degree of sleepiness and, if appropriate, advised to avoid driving or any other potentially dangerous activity. Prescribers should also be aware that patients may not acknowledge sleepiness or drowsiness until directly questioned about drowsiness or sleepiness during specific activities.

Psychiatric Symptoms

Psychiatric adverse experiences have been reported in patients treated with modafinil. Postmarketing adverse events associated with the use of modafinil have included mania, delusions, hallucinations, suicidal ideation and aggression, some resulting in hospitalization. Many, but not all, patients had a prior psychiatric history. One healthy male volunteer developed ideas of reference, paranoid delusions, and auditory hallucinations in association with multiple daily 600 mg doses of modafinil and sleep deprivation. There was no evidence of psychosis 36 hours after drug discontinuation.

In the adult modafinil controlled trials database, psychiatric symptoms resulting in treatment discontinuation (at a frequency >0.3%) and reported more often in patients treated with modafinil compared to those treated with placebo were anxiety (1%), nervousness (1%), insomnia (<1%), confusion (<1%), agitation (<1%), and depression (<1%). Caution should be exercised when Provigil is given to patients with a history of psychosis, depression, or mania. Consideration should be given to the possible emergence or exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms in patients treated with Provigil. If psychiatric symptoms develop in association with Provigil administration, consider discontinuing Provigil.

Precautions

Diagnosis of Sleep Disorders

Provigil should be used only in patients who have had a complete evaluation of their excessive sleepiness, and in whom a diagnosis of either narcolepsy, OSAHS, and/or SWSD has been made in accordance with ICSD or DSM diagnostic criteria (See Clinical Trails). Such an evaluation usually consists of a complete history and physical examination, and it may be supplemented with testing in a laboratory setting. Some patients may have more than one sleep disorder contributing to their excessive sleepiness (e.g., OSAHS and SWSD coincident in the same patient).

General

Although modafinil has not been shown to produce functional impairment, any drug affecting the CNS may alter judgment, thinking or motor skills. Patients should be cautioned about operating an automobile or other hazardous machinery until they are reasonably certain that Provigil therapy will not adversely affect their ability to engage in such activities.

CPAP Use in Patients with OSAHS

In OSAHS, Provigil is indicated as an adjunct to standard treatment(s) for the underlying obstruction. If continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the treatment of choice for a patient, a maximal effort to treat with CPAP for an adequate period of time should be made prior to initiating Provigil. If Provigil is used adjunctively with CPAP, the encouragement of and periodic assessment of CPAP compliance is necessary.

Cardiovascular System

Modafinil has not been evaluated in patients with a recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable angina, and such patients should be treated with caution.

In clinical studies of Provigil, signs and symptoms including chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea and transient ischemic T-wave changes on ECG were observed in three subjects in association with mitral valve prolapse or left ventricular hypertrophy. It is recommended that Provigil tablets not be used in patients with a history of left ventricular hypertrophy or in patients with mitral valve prolapse who have experienced the mitral valve prolapse syndrome when previously receiving CNS stimulants. Such signs may include but are not limited to ischemic ECG changes, chest pain, or arrhythmia. If new onset of any of these symptoms occurs, consider cardiac evaluation.

Blood pressure monitoring in short-term (<3 months) controlled trials showed no clinically significant changes in mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure in patients receiving Provigil as compared to placebo. However, a retrospective analysis of the use of antihypertensive medication in these studies showed that a greater proportion of patients on Provigil required new or increased use of antihypertensive medications (2.4%) compared to patients on placebo (0.7%). The differential use was slightly larger when only studies in OSAHS were included, with 3.4% of patients on Provigil and 1.1% of patients on placebo requiring such alterations in the use of antihypertensive medication. Increased monitoring of blood pressure may be appropriate in patients on Provigil.

Patients Using Steroidal Contraceptives

The effectiveness of steroidal contraceptives may be reduced when used with Provigil tablets and for one month after discontinuation of therapy (See Precautions, Drug Interactions). Alternative or concomitant methods of contraception are recommended for patients treated with Provigil tablets, and for one month after discontinuation of Provigil.

Patients Using Cyclosporine

The blood levels of cyclosporine may be reduced when used with Provigil (See Precautions, Drug Interactions). Monitoring of circulating cyclosporine concentrations and appropriate dosage adjustment for cyclosporine should be considered when these drugs are used concomitantly.

Patients with Severe Hepatic Impairment

In patients with severe hepatic impairment, with or without cirrhosis (See Clinical Pharmacology), Provigil should be administered at a reduced dose (See Dosage and Administration).

Patients with Severe Renal Impairment

There is inadequate information to determine safety and efficacy of dosing in patients with severe renal impairment. (For pharmacokinetics in renal impairment, see Clinical Pharmacology.)

Elderly Patients

In elderly patients, elimination of modafinil and its metabolites may be reduced as a consequence of aging. Therefore, consideration should be given to the use of lower doses in this population. (See Clinical Pharmacology and Dosage and Administration).

Information for Patients

Physicians are advised to discuss the following issues with patients for whom they prescribe Provigil.

Provigil is indicated for patients who have abnormal levels of sleepiness. Provigil has been shown to improve, but not eliminate this abnormal tendency to fall asleep. Therefore, patients should not alter their previous behavior with regard to potentially dangerous activities (e.g., driving, operating machinery) or other activities requiring appropriate levels of wakefulness, until and unless treatment with Provigil has been shown to produce levels of wakefulness that permit such activities. Patients should be advised that Provigil is not a replacement for sleep.

Patients should be informed that it may be critical that they continue to take their previously prescribed treatments (e.g., patients with OSAHS receiving CPAP should continue to do so).

Patients should be informed of the availability of a patient information leaflet, and they should be instructed to read the leaflet prior to taking Provigil.

Patients should be advised to contact their physician if they experience chest pain, rash, depression, anxiety, or signs of psychosis or mania.

Pregnancy

Patients should be advised to notify their physician if they become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during therapy. Patients should be cautioned regarding the potential increased risk of pregnancy when using steroidal contraceptives (including depot or implantable contraceptives) with Provigil and for one month after discontinuation of therapy (See Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility and Pregnancy).

Nursing

Patients should be advised to notify their physician if they are breastfeeding an infant.

Concomitant Medication

Patients should be advised to inform their physician if they are taking, or plan to take, any prescription or over-the-counter drugs, because of the potential for interactions between Provigil and other drugs.

Alcohol

Patients should be advised that the use of Provigil in combination with alcohol has not been studied. Patients should be advised that it is prudent to avoid alcohol while taking Provigil.

Allergic Reactions

Patients should be advised to stop taking Provigil and to notify their physician if they develop a rash, hives, mouth sores, blisters, peeling skin, trouble swallowing or breathing or a related allergic phenomenon.

Drug Interactions

CNS Active Drugs

Methylphenidate

In a single-dose study in healthy volunteers, simultaneous administration of modafinil (200 mg) with methylphenidate (40 mg) did not cause any significant alterations in the pharmacokinetics of either drug. However, the absorption of Provigil may be delayed by approximately one hour when coadministered with methylphenidate.

In a multiple-dose, steady-state study in healthy volunteers, modafinil was administered once daily at 200 mg/day for 7 days followed by 400 mg/day for 21 days. Administration of methylphenidate (20 mg/day) during days 22-28 of modafinil treatment 8 hours after the daily dose of modafinil did not cause any significant alterations in the pharmacokinetics of modafinil.

Dextroamphetamine

In a single dose study in healthy volunteers, simultaneous administration of modafinil (200 mg) with dextroamphetamine (10 mg) did not cause any significant alterations in the pharmacokinetics of either drug. However, the absorption of Provigil may be delayed by approximately one hour when coadministered with dextroamphetamine.

In a multiple-dose, steady-state study in healthy volunteers, modafinil was administered once daily at 200 mg/day for 7 days followed by 400 mg/day for 21 days. Administration of dextroamphetamine (20 mg/day) during days 22-28 of modafinil treatment 7 hours after the daily dose of modafinil did not cause any significant alterations in the pharmacokinetics of modafinil.

Clomipramine

The coadministration of a single dose of clomipramine (50 mg) on the first of three days of treatment with modafinil (200 mg/day) in healthy volunteers did not show an effect on the pharmacokinetics of either drug. However, one incident of increased levels of clomipramine and its active metabolite desmethylclomipramine has been reported in a patient with narcolepsy during treatment with modafinil.

Triazolam

In the drug interaction study between Provigil and ethinyl estradiol (EE2), on the same days as those for the plasma sampling for EE2 pharmacokinetics, a single dose of triazolam (0.125 mg) was also administered. Mean Cmax and AUC0-β of triazolam were decreased by 42% and 59%, respectively, and its elimination half-life was decreased by approximately an hour after the modafinil treatment.

Monoamine Oxidase (MAO) Inhibitors

Interaction studies with monoamine oxidase inhibitors have not been performed. Therefore, caution should be used when concomitantly administering MAO inhibitors and modafinil.

Other Drugs

Warfarin

There were no significant changes in the pharmacokinetic profiles of R- and S-warfarin in healthy subjects given a single dose of racemic warfarin (5 mg) following chronic administration of modafinil (200 mg/day for 7 days followed by 400 mg/day for 27 days) relative to the profiles in subjects given placebo. However, more frequent monitoring of prothrombin times/INR is advisable whenever Provigil is coadministered with warfarin (See Clinical Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics,Drug-Drug Interactions).

Ethinyl Estradiol

Administration of modafinil to female volunteers once daily at 200 mg/day for 7 days followed by 400 mg/day for 21 days resulted in a mean 11% decrease in Cmax and 18% decrease in AUC0-24 of ethinyl estradiol (EE2; 0.035 mg; administered orally with norgestimate). There was no apparent change in the elimination rate of ethinyl estradiol.

Cyclosporine

One case of an interaction between modafinil and cyclosporine, a substrate of CYP3A4, has been reported in a 41 year old woman who had undergone an organ transplant. After one month of administration of 200 mg/day of modafinil, cyclosporine blood levels were decreased by 50%. The interaction was postulated to be due to the increased metabolism of cyclosporine, since no other factor expected to affect the disposition of the drug had changed. Dosage adjustment for cyclosporine may be needed.

Potential Interactions with Drugs That Inhibit, Induce, or are Metabolized by Cytochrome P-450 Isoenzymes and Other Hepatic Enzymes

In in vitro studies using primary human hepatocyte cultures, modafinil was shown to slightly induce CYP1A2, CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 in a concentration-dependent manner. Although induction results based on in vitro experiments are not necessarily predictive of response in vivo, caution needs to be exercised when Provigil is coadministered with drugs that depend on these three enzymes for their clearance. Specifically, lower blood levels of such drugs could result (See Other Drugs, Cyclosporineabove).

The exposure of human hepatocytes to modafinil in vitro produced an apparent concentration-related suppression of expression of CYP2C9 activity suggesting that there is a potential for a metabolic interaction between modafinil and the substrates of this enzyme (e.g., S-warfarin and phenytoin). In a subsequent clinical study in healthy volunteers, chronic modafinil treatment did not show a significant effect on the single-dose pharmacokinetics of warfarin when compared to placebo (see Precautions, Drug Interactions,Warfarin).

In vitro studies using human liver microsomes showed that modafinil reversibly inhibited CYP2C19 at pharmacologically relevant concentrations of modafinil. CYP2C19 is also reversibly inhibited, with similar potency, by a circulating metabolite, modafinil sulfone. Although the maximum plasma concentrations of modafinil sulfone are much lower than those of parent modafinil, the combined effect of both compounds could produce sustained partial inhibition of the enzyme. Drugs that are largely eliminated via CYP2C19 metabolism, such as diazepam, propranolol, phenytoin (also via CYP2C9) or S-mephenytoin may have prolonged elimination upon coadministration with Provigil and may require dosage reduction and monitoring for toxicity.

Tricyclic antidepressants

CYP2C19 also provides an ancillary pathway for the metabolism of certain tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., clomipramine and desipramine) that are primarily metabolized by CYP2D6. In tricyclic-treated patients deficient in CYP2D6 (i.e., those who are poor metabolizers of debrisoquine; 7-10% of the Caucasian population; similar or lower in other populations), the amount of metabolism by CYP2C19 may be substantially increased. Provigil may cause elevation of the levels of the tricyclics in this subset of patients. Physicians should be aware that a reduction in the dose of tricyclic agents might be needed in these patients.

In addition, due to the partial involvement of CYP3A4 in the metabolic elimination of modafinil, coadministration of potent inducers of CYP3A4 (e.g., carbamazepine, phenobarbital, rifampin) or inhibitors of CYP3A4 (e.g., ketoconazole, itraconazole) could alter the plasma levels of modafinil.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

Carcinogenicity studies were conducted in which modafinil was administered in the diet to mice for 78 weeks and to rats for 104 weeks at doses of 6, 30, and 60 mg/kg/day. The highest dose studied is 1.5 (mouse) or 3 (rat) times greater than the recommended adult human daily dose of modafinil (200 mg) on a mg/m2 basis. There was no evidence of tumorigenesis associated with modafinil administration in these studies. However, since the mouse study used an inadequate high dose that was not representative of a maximum tolerated dose, a subsequent carcinogenicity study was conducted in the Tg.AC transgenic mouse. Doses evaluated in the Tg.AC assay were 125, 250, and 500 mg/kg/day, administered dermally. There was no evidence of tumorigenicity associated with modafinil administration; however, this dermal model may not adequately assess the carcinogenic potential of an orally administered drug.

Mutagenesis

Modafinil demonstrated no evidence of mutagenic or clastogenic potential in a series of in vitro (i.e., bacterial reverse mutation assay, mouse lymphoma tk assay, chromosomal aberration assay in human lymphocytes, cell transformation assay in BALB/3T3 mouse embryo cells) assays in the absence or presence of metabolic activation, or in vivo (mouse bone marrow micronucleus) assays. Modafinil was also negative in the unscheduled DNA synthesis assay in rat hepatocytes.

Impairment of Fertility

Oral administration of modafinil (doses of up to 480 mg/kg/day) to male and female rats prior to and throughout mating, and continuing in females through day 7 of gestation produced an increase in the time to mate at the highest dose; no effects were observed on other fertility or reproductive parameters. The no-effect dose of 240 mg/kg/day was associated with a plasma modafinil exposure (AUC) approximately equal to that in humans at the recommended dose of 200 mg.

Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C:

In studies conducted in rats and rabbits, developmental toxicity was observed at clinically relevant exposures.

Modafinil (50, 100, or 200 mg/kg/day) administered orally to pregnant rats throughout the period of organogenesis caused, in the absence of maternal toxicity, an increase in resorptions and an increased incidence of visceral and skeletal variations in the offspring at the highest dose. The higher no-effect dose for rat embryofetal developmental toxicity was associated with a plasma modafinil exposure approximately 0.5 times the AUC in humans at the recommended daily dose (RHD) of 200 mg. However, in a subsequent study of up to 480 mg/kg/day (plasma modafinil exposure approximately 2 times the AUC in humans at the RHD) no adverse effects on embryofetal development were observed.

Modafinil administered orally to pregnant rabbits throughout the period of organogenesis at doses of 45, 90, and 180 mg/kg/day increased the incidences of fetal structural alterations and embryofetal death at the highest dose. The highest no-effect dose for developmental toxicity was associated with a plasma modafinil AUC approximately equal to the AUC in humans at the RHD.

Oral administration of armodafinil (the R-enantiomer of modafinil; 60, 200, or 600 mg/kg/day) to pregnant rats throughout the period of organogenesis resulted in increased incidences of fetal visceral and skeletal variations at the intermediate dose or greater and decreased fetal body weights at the highest dose. The no-effect dose for rat embryofetal developmental toxicity was associated with a plasma armodafinil exposure (AUC) approximately one-tenth times the AUC for armodafinil in humans treated with modafinil at the RHD.

Modafinil administration to rats throughout gestation and lactation at oral doses of up to 200 mg/kg/day resulted in decreased viability in the offspring at doses greater than 20 mg/kg/day (plasma modafinil AUC approximately 0.1 times the AUC in humans at the RHD). No effects on postnatal developmental and neurobehavioral parameters were observed in surviving offspring.

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Two cases of intrauterine growth retardation and one case of spontaneous abortion have been reported in association with armodafinil and modafinil. Although the pharmacology of modafinil and armodafinil is not identical to that of the sympathomimetic amines, they do share some pharmacologic properties with this class. Certain of these drugs have been associated with intrauterine growth retardation and spontaneous abortions. Whether the cases reported are drug-related is unknown.

Modafinil should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Labor and Delivery

The effect of modafinil on labor and delivery in humans has not been systematically investigated.

Nursing Mothers

It is not known whether modafinil or its metabolites are excreted in human milk. Because many drugs are excreted in human milk, caution should be exercised when Provigil tablets are administered to a nursing woman.

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients, below age 16, have not been established. Serious skin rashes, including erythema multiforme major (EMM) and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) have been associated with modafinil use in pediatric patients (see Warnings, Serious Rash, including Stevens-Johnson Syndrome).

In a controlled 6-week study, 165 pediatric patients (aged 5-17 years) with narcolepsy were treated with modafinil (n=123), or placebo (n=42). There were no statistically significant differences favoring modafinil over placebo in prolonging sleep latency as measured by MSLT, or in perceptions of sleepiness as determined by the clinical global impression-clinician scale (CGI-C).

In the controlled and open-label clinical studies, treatment emergent adverse events of the psychiatric and nervous system included Tourette's syndrome, insomnia, hostility, increased cataplexy, increased hypnagogic hallucinations and suicidal ideation. Transient leukopenia, which resolved without medical intervention, was also observed. In the controlled clinical study, 3 of 38 girls, ages 12 or older, treated with modafinil experienced dysmenorrhea compared to 0 of 10 girls who received placebo.

Geriatric Use

Safety and effectiveness in individuals above 65 years of age have not been established. Experience in a limited number of patients who were greater than 65 years of age in clinical trials showed an incidence of adverse experiences similar to other age groups.

Adverse Reactions

Modafinil has been evaluated for safety in over 3500 patients, of whom more than 2000 patients with excessive sleepiness associated with primary disorders of sleep and wakefulness were given at least one dose of modafinil. In clinical trials, modafinil has been found to be generally well tolerated and most adverse experiences were mild to moderate.

The most commonly observed adverse events (≥5%) associated with the use of Provigil more frequently than placebo-treated patients in the placebo-controlled clinical studies in primary disorders of sleep and wakefulness were headache, nausea, nervousness, rhinitis, diarrhea, back pain, anxiety, insomnia, dizziness, and dyspepsia. The adverse event profile was similar across these studies.

In the placebo-controlled clinical trials, 74 of the 934 patients (8%) who received Provigil discontinued due to an adverse experience compared to 3% of patients that received placebo. The most frequent reasons for discontinuation that occurred at a higher rate for Provigil than placebo patients were headache (2%), nausea, anxiety, dizziness, insomnia, chest pain and nervousness (each <1%). In a Canadian clinical trial, a 35 year old obese narcoleptic male with a prior history of syncopal episodes experienced a 9-second episode of asystole after 27 days of modafinil treatment (300 mg/day in divided doses).

Incidence in Controlled Trials

The following table (Table 3) presents the adverse experiences that occurred at a rate of 1% or more and were more frequent in adult patients treated with Provigil than in placebo-treated patients in the principal, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

The prescriber should be aware that the figures provided below cannot be used to predict the frequency of adverse experiences in the course of usual medical practice, where patient characteristics and other factors may differ from those occurring during clinical studies. Similarly, the cited frequencies cannot be directly compared with figures obtained from other clinical investigations involving different treatments, uses, or investigators. Review of these frequencies, however, provides prescribers with a basis to estimate the relative contribution of drug and non-drug factors to the incidence of adverse events in the population studied.

| Body System | Preferred Term | Modafinil (n = 934) |

Placebo (n = 567) |

| * Six double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical studies in narcolepsy, OSAHS, and SWSD.

1 Events reported by at least 1% of patients treated with Provigil that were more frequent than in the placebo group are included; incidence is rounded to the nearest 1%. The adverse experience terminology is coded using a standard modified COSTART Dictionary. Events for which the Provigil incidence was at least 1%, but equal to or less than placebo are not listed in the table. These events included the following: infection, pain, accidental injury, abdominal pain, hypothermia, allergic reaction, asthenia, fever, viral infection, neck pain, migraine, abnormal electrocardiogram, hypotension, tooth disorder, vomiting, periodontal abscess, increased appetite, ecchymosis, hyperglycemia, peripheral edema, weight loss, weight gain, myalgia, leg cramps, arthritis, cataplexy, thinking abnormality, sleep disorder, increased cough, sinusitis, dyspnea, bronchitis, rash, conjunctivitis, ear pain, dysmenorrhea4, urinary tract infection. 2 Elevated liver enzymes. 3 Oro-facial dyskinesias. 4 Incidence adjusted for gender. |

|||

| Body as a Whole | Headache | 34% | 23% |

| Back Pain | 6% | 5% | |

| Flu Syndrome | 4% | 3% | |

| Chest Pain | 3% | 1% | |

| Chills | 1% | 0% | |

| Neck Rigidity | 1% | 0% | |

| Cardiovascular | Hypertension | 3% | 1% |

| Tachycardia | 2% | 1% | |

| Palpitation | 2% | 1% | |

| Vasodilatation | 2% | 0% | |

| Digestive | Nausea | 11% | 3% |

| Diarrhea | 6% | 5% | |

| Dyspepsia | 5% | 4% | |

| Dry Mouth | 4% | 2% | |

| Anorexia | 4% | 1% | |

| Constipation | 2% | 1% | |

| Abnormal Liver Function2 | 2% | 1% | |

| Flatulence | 1% | 0% | |

| Mouth Ulceration | 1% | 0% | |

| Thirst | 1% | 0% | |

| Hemic/Lymphatic | Eosinophilia | 1% | 0% |

| Metabolic/Nutritional | Edema | 1% | 0% |

| Nervous | Nervousness | 7% | 3% |

| Insomnia | 5% | 1% | |

| Anxiety | 5% | 1% | |

| Dizziness | 5% | 4% | |

| Depression | 2% | 1% | |

| Paresthesia | 2% | 0% | |

| Somnolence | 2% | 1% | |

| Hypertonia | 1% | 0% | |

| Dyskinesia3 | 1% | 0% | |

| Hyperkinesia | 1% | 0% | |

| Agitation | 1% | 0% | |

| Confusion | 1% | 0% | |

| Tremor | 1% | 0% | |

| Emotional Lability | 1% | 0% | |

| Vertigo | 1% | 0% | |

| Respiratory | Rhinitis | 7% | 6% |

| Pharyngitis | 4% | 2% | |

| Lung Disorder | 2% | 1% | |

| Epistaxis | 1% | 0% | |

| Asthma | 1% | 0% | |

| Skin/Appendages | Sweating | 1% | 0% |

| Herpes Simplex | 1% | 0% | |

| Special Senses | Amblyopia | 1% | 0% |

| Abnormal Vision | 1% | 0% | |

| Taste Perversion | 1% | 0% | |

| Eye Pain | 1% | 0% | |

| Urogenital | Urine Abnormality | 1% | 0% |

| Hematuria | 1% | 0% | |

| Pyuria | 1% | 0% | |

Dose Dependency of Adverse Events

In the adult placebo-controlled clinical trials which compared doses of 200, 300, and 400 mg/day of Provigil and placebo, the only adverse events that were clearly dose related were headache and anxiety.

Vital Sign Changes

While there was no consistent change in mean values of heart rate or systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the requirement for antihypertensive medication was slightly greater in patients on Provigil compared to placebo (See Precautions).

Weight Changes

There were no clinically significant differences in body weight change in patients treated with Provigil compared to placebo-treated patients in the placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Laboratory Changes

Clinical chemistry, hematology, and urinalysis parameters were monitored in Phase 1, 2, and 3 studies. In these studies, mean plasma levels of gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (AP) were found to be higher following administration of Provigil, but not placebo. Few subjects, however, had GGT or AP elevations outside of the normal range. Shifts to higher, but not clinically significantly abnormal, GGT and AP values appeared to increase with time in the population treated with Provigil in the Phase 3 clinical trials. No differences were apparent in alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total protein, albumin, or total bilirubin.

ECG Changes

No treatment-emergent pattern of ECG abnormalities was found in placebo-controlled clinical trials following administration of Provigil.

Postmarketing Reports

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post-approval use of Provigil. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure. Decisions to include these reactions in labeling are typically based on one or more of the following factors: (1) seriousness of the reaction, (2) frequency of the reporting, or (3) strength of causal connection to Provigil.

Hematologic: agranulocytosis

Drug Abuse and Dependence

Controlled Substance Class

Modafinil (Provigil) is listed in Schedule IV of the Controlled Substances Act.

Abuse Potential and Dependence

In addition to its wakefulness-promoting effect and increased locomotor activity in animals, in humans, Provigil produces psychoactive and euphoric effects, alterations in mood, perception, thinking and feelings typical of other CNS stimulants. In in vitro binding studies, modafinil binds to the dopamine reuptake site and causes an increase in extracellular dopamine, but no increase in dopamine release. Modafinil is reinforcing, as evidenced by its self-administration in monkeys previously trained to self-administer cocaine. In some studies, modafinil was also partially discriminated as stimulant-like. Physicians should follow patients closely, especially those with a history of drug and/or stimulant (e.g., methylphenidate, amphetamine, or cocaine) abuse. Patients should be observed for signs of misuse or abuse (e.g., incrementation of doses or drug-seeking behavior).

The abuse potential of modafinil (200, 400, and 800 mg) was assessed relative to methylphenidate (45 and 90 mg) in an inpatient study in individuals experienced with drugs of abuse. Results from this clinical study demonstrated that modafinil produced psychoactive and euphoric effects and feelings consistent with other scheduled CNS stimulants (methylphenidate).

Withdrawal

The effects of modafinil withdrawal were monitored following 9 weeks of modafinil use in one US Phase 3 controlled clinical trial. No specific symptoms of withdrawal were observed during 14 days of observation, although sleepiness returned in narcoleptic patients.

Overdosage

Human Experience

In clinical trials, a total of 151 protocol-specified doses ranging from 1000 to 1600 mg/day (5 to 8 times the recommended daily dose of 200 mg) have been administered to 32 subjects, including 13 subjects who received doses of 1000 or 1200 mg/day for 7 to 21 consecutive days. In addition, several intentional acute overdoses occurred; the two largest being 4500 mg and 4000 mg taken by two subjects participating in foreign depression studies. None of these study subjects experienced any unexpected or life-threatening effects. Adverse experiences that were reported at these doses included excitation or agitation, insomnia, and slight or moderate elevations in hemodynamic parameters. Other observed high-dose effects in clinical studies have included anxiety, irritability, aggressiveness, confusion, nervousness, tremor, palpitations, sleep disturbances, nausea, diarrhea and decreased prothrombin time.

From post-marketing experience, there have been no reports of fatal overdoses involving modafinil alone (doses up to 12 grams). Overdoses involving multiple drugs, including modafinil, have resulted in fatal outcomes. Symptoms most often accompanying modafinil overdose, alone or in combination with other drugs have included: insomnia; central nervous system symptoms such as restlessness, disorientation, confusion, excitation and hallucination; digestive changes such as nausea and diarrhea; and cardiovascular changes such as tachycardia, bradycardia, hypertension and chest pain.

Cases of accidental ingestion/overdose have been reported in children as young as 11 months of age. The highest reported accidental ingestion on a mg/kg basis occurred in a three-year-old boy who ingested 800-1000 mg (50-63 mg/kg) of modafinil. The child remained stable. The symptoms associated with overdose in children were similar to those observed in adults.

Overdose Management

No specific antidote to the toxic effects of modafinil overdose has been identified to date. Such overdoses should be managed with primarily supportive care, including cardiovascular monitoring. If there are no contraindications, induced emesis or gastric lavage should be considered. There are no data to suggest the utility of dialysis or urinary acidification or alkalinization in enhancing drug elimination. The physician should consider contacting a poison-control center on the treatment of any overdose.

Dosage and Administration

The recommended dose of Provigil is 200 mg given once a day.

For patients with narcolepsy and OSAHS, Provigil should be taken as a single dose in the morning.

For patients with SWSD, Provigil should be taken approximately 1 hour prior to the start of their work shift.

Doses up to 400 mg/day, given as a single dose, have been well tolerated, but there is no consistent evidence that this dose confers additional benefit beyond that of the 200 mg dose (See Clinical Pharmacology and Clinical Trails).

General Considerations

Dosage adjustment should be considered for concomitant medications that are substrates for CYP3A4, such as triazolam and cyclosporine (See Precautions, Drug Interactions).

Drugs that are largely eliminated via CYP2C19 metabolism, such as diazepam, propranolol, phenytoin (also via CYP2C9) or S-mephenytoin may have prolonged elimination upon coadministration with Provigil and may require dosage reduction and monitoring for toxicity.

In patients with severe hepatic impairment, the dose of Provigil should be reduced to one-half of that recommended for patients with normal hepatic function (See CClinical Pharmacology and Precautions).

There is inadequate information to determine safety and efficacy of dosing in patients with severe renal impairment (See Clinical Pharmacology and Precautions).

In elderly patients, elimination of Provigil and its metabolites may be reduced as a consequence of aging. Therefore, consideration should be given to the use of lower doses in this population (See Clinical Pharmacology and Precautions).

How Supplied

Provigil® (modafinil) Tablets

100 mg: Each capsule-shaped, white, uncoated tablet is debossed with "Provigil" on one side and "100 MG" on the other.

NDC 63459-101-01 - Bottles of 100

200 mg: Each capsule-shaped, white, scored, uncoated tablet is debossed with "Provigil" on one side and "200 MG" on the other.

NDC 63459-201-01 - Bottles of 100

Store at 20° - 25° C (68° - 77° F).

Manufactured for:

Cephalon, Inc.

Frazer, PA 19355

U.S. Patent Nos. RE37,516 / 4,927,855

© Cephalon, Inc., 2008. All rights reserved

PROV-011

Last Updated: 03/08

Provigil (modafinil) patient information sheet (in plain English)

Detailed Info on Signs, Symptoms, Causes, Treatments of Sleep Disorders

The information in this monograph is not intended to cover all possible uses, directions, precautions, drug interactions or adverse effects. This information is generalized and is not intended as specific medical advice. If you have questions about the medicines you are taking or would like more information, check with your doctor, pharmacist, or nurse.

back to:

~ all articles on sleeping disorders

APA Reference

Staff, H.

(2019, March 31). Provigil: Treatment for Wakefulness (Full Prescribing Information), HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2026, February 23 from https://www.healthyplace.com/other-info/sleep-disorders/provigil-treatment-for-wakefulness-full-prescribing-information